Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

-

Congratulations TugboatEng on being selected by the Eng-Tips community for having the most helpful posts in the forums last week. Way to Go!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

4 Cycle Energy Question 2

- Thread starter bcavender

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

GregLocock

Automotive

As a thought experiment run an engine from BDC, all valves closed, no fuel. The charge air will compress on the way up, and expand on the way down. If there was no heat transfer to the walls etc it would be 100% efficient.

Cheers

Greg Locock

New here? Try reading these, they might help FAQ731-376

Cheers

Greg Locock

New here? Try reading these, they might help FAQ731-376

BrianPetersen

Mechanical

In the absence of heat transfer and friction - i.e. considering the "ideal cycle" - the air compressed in stroke 2 simply acts as a spring. All of the mechanical energy that it took out of the crankshaft in the compression stroke is returned back to the crankshaft in the following expansion stroke.

Real-world friction and heat transfer mean that the energy returned on the expansion stroke will be somewhat less than what was taken up on the compression stroke. How much less ... depends on about a million factors that you haven't asked about or specified.

Real-world friction and heat transfer mean that the energy returned on the expansion stroke will be somewhat less than what was taken up on the compression stroke. How much less ... depends on about a million factors that you haven't asked about or specified.

- Thread starter

- #5

Intuitively I thought that a good deal of the compression work might be returned, but (with no prior experience with this) I was looking to learn quantitatively just how much the loss this part of the cycle contributed to total ICE system losses.

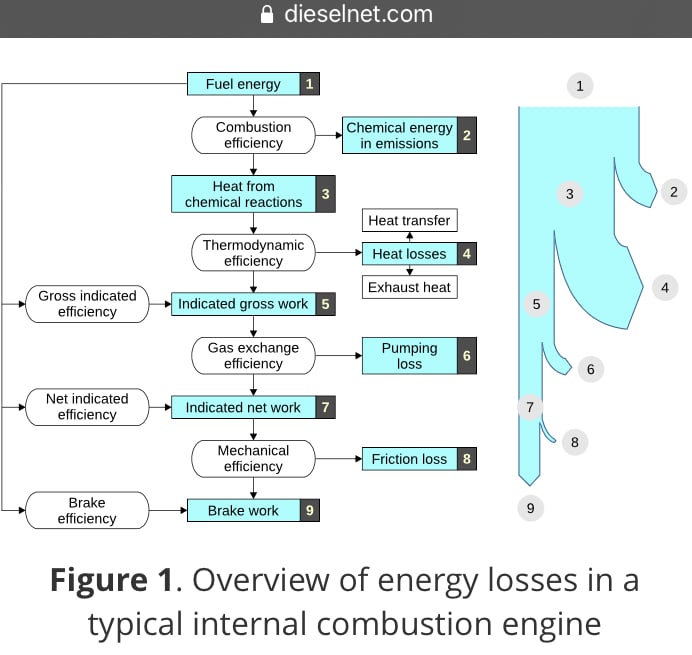

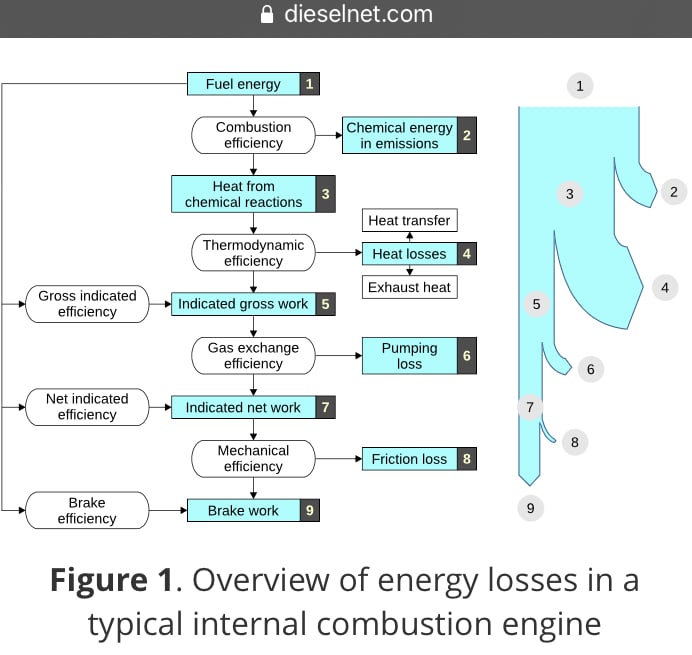

With a little more searching I came across a very helpful diagram at dieselnet.com that shows ICE’s relative energy losses from fuel input to brake output.

It categorizes ICE losses into four groups of which ‘Pumping Loss’ appears to be not an insignificant loss, but then again it’s far smaller than the size of thermodynamic losses due to its short adiabatic character as pointed out by group comments.

It was interesting to see that these four loss groups appear to to consume 75-80% of the total energy input.

That was higher than I expected, so my next step is to dig a little deeper into the numbers to see if dieselnet is spot on or more pessimistic than what can be practically achieved in the real world with different designs, fuels, etc.

Appreciate the comments and any further suggestions for digging deeper!

B

With a little more searching I came across a very helpful diagram at dieselnet.com that shows ICE’s relative energy losses from fuel input to brake output.

It categorizes ICE losses into four groups of which ‘Pumping Loss’ appears to be not an insignificant loss, but then again it’s far smaller than the size of thermodynamic losses due to its short adiabatic character as pointed out by group comments.

It was interesting to see that these four loss groups appear to to consume 75-80% of the total energy input.

That was higher than I expected, so my next step is to dig a little deeper into the numbers to see if dieselnet is spot on or more pessimistic than what can be practically achieved in the real world with different designs, fuels, etc.

Appreciate the comments and any further suggestions for digging deeper!

B

That would leave only 20 - 25% for shaft work ie a Thermal Efficiency of 20 - 25%.bcavender said:It was interesting to see that these four loss groups appear to to consume 75-80% of the total energy input.

Peak TE for diesel engines is 30 - 50% but can be much lower at part loads - eg zero at idle.

je suis charlie

BrianPetersen

Mechanical

That should be considered an illustrative, conceptual sketch not meant to imply actual numbers. Even for a single engine, that distribution will vary depending upon operating conditions. At idle, useful output work (and thus, thermal efficiency) is zero. On a modern emission controlled engine with reasonably accurate fuel metering, the percentage lost to chemical energy in the emissions should be low.

- Thread starter

- #8

-

1

- #9

BrianPetersen

Mechanical

This won't be an "efficiency curve". For a given engine it will be a complex multidimensional map that is a function of the mechanical design of the engine and its calibration and, perhaps more significantly than anything else, its operating conditions.

The one that's most of interest is the mechanical power out relative to the chemical energy in. That is called the "brake specific fuel consumption" (BSFC). Look up BSFC charts of a few engines and you'll see what I mean. They take the form of a chart with the main variables RPM on one axis and torque or BMEP (brake mean effective pressure) on the other axis and you look up what the fuel consumption is on that chart ... except that this one chart will be particular to specified barometric pressure, temperature, coolant temperature, etc., and if you change those things (significantly), it changes the chart. This is NOT simple. For a given engine, the RPM and the BMEP are the two main influencing factors but the others are not zero.

As for what portion goes out the tailpipe and what portion goes out the radiator ... it won't be completely out of the ballpark to estimate that whatever energy input doesn't come out as shaft power, is split more-or-less evenly between cooling system and exhaust pipe, with the chemical-energy lost to the exhaust negligible on a modern engine if the catalyst is taken into account as being part of the complete engine. But ... so what? Neither are useful to you aside from heating the interior in winter, and perhaps being necessary to size the cooling system components. Design features such as integral exhaust manifolds cast into the cylinder head tip the balance towards the heat going to the radiator (and making the engine warm up faster) because they're surrounded by cooling jackets inside the cylinder head.

The one that's most of interest is the mechanical power out relative to the chemical energy in. That is called the "brake specific fuel consumption" (BSFC). Look up BSFC charts of a few engines and you'll see what I mean. They take the form of a chart with the main variables RPM on one axis and torque or BMEP (brake mean effective pressure) on the other axis and you look up what the fuel consumption is on that chart ... except that this one chart will be particular to specified barometric pressure, temperature, coolant temperature, etc., and if you change those things (significantly), it changes the chart. This is NOT simple. For a given engine, the RPM and the BMEP are the two main influencing factors but the others are not zero.

As for what portion goes out the tailpipe and what portion goes out the radiator ... it won't be completely out of the ballpark to estimate that whatever energy input doesn't come out as shaft power, is split more-or-less evenly between cooling system and exhaust pipe, with the chemical-energy lost to the exhaust negligible on a modern engine if the catalyst is taken into account as being part of the complete engine. But ... so what? Neither are useful to you aside from heating the interior in winter, and perhaps being necessary to size the cooling system components. Design features such as integral exhaust manifolds cast into the cylinder head tip the balance towards the heat going to the radiator (and making the engine warm up faster) because they're surrounded by cooling jackets inside the cylinder head.

- Thread starter

- #10

Brian,

WOW! Now there is a treasure trove of real data I have never seen. EXCELLENT!!!

Just looking at a few of the BSFC charts the search turned up shows an amazing wealth of data on a broad spectrum of specific engines under a wide set of operating conditions.

Thank you for the pointer and the chance to advance the learning process!!!

I really appreciate your kind assistance!!! You are on top of your game![[thumbsup2] [thumbsup2] [thumbsup2]](/data/assets/smilies/thumbsup2.gif)

B

WOW! Now there is a treasure trove of real data I have never seen. EXCELLENT!!!

Just looking at a few of the BSFC charts the search turned up shows an amazing wealth of data on a broad spectrum of specific engines under a wide set of operating conditions.

Thank you for the pointer and the chance to advance the learning process!!!

I really appreciate your kind assistance!!! You are on top of your game

![[thumbsup2] [thumbsup2] [thumbsup2]](/data/assets/smilies/thumbsup2.gif)

B

-

1

- #11

- Thread starter

- #12

bcavendar said:It categorizes ICE losses into four groups of which ‘Pumping Loss’ appears to be not an insignificant loss

In addition to the good information provided above, you have to think carefully about that term ('pumping loss') as well.

Pumping losses are not losses due to some energy path out of the cylinder during compression after the valves are closed. When an engine is operating at speed, the actual energy lost between BDC and TDC and back again are very small; the processes mentioned by others above (heat transfer, etc) are happening, but they are not instantaneous. In the aggregate, over millions of 4-stroke cycles, they add up; but if you're looking at a single cycle they are very, very small.

Anyway. Moving air past the valves and into the cylinder and then out again after combustion takes work (the air doesn't just pump itself). There's air in the intake manifold which has already passed the throttle, but to make it into the cylinder it needs to get sucked down an intake runner which may be short or long, may have a small or large diameter, etc. The energy it takes to pump the air is lost. That's what pumping losses are.

Pumping losses can be estimated if you know an engine's volumetric efficiency, but an assessment of actual real-world VE is similar to Brian's description of BMEP plots in that there are many variables and they all can have a dramatic effect on the actual value; there isn't just a simple curve to plot.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 15

- Views

- 643

- Locked

- Question

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 2K

- Locked

- Question

- Replies

- 17

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 690