adrich91

Chemical

- Oct 6, 2024

- 13

Good morning,

I have a doubt about the calculation of the installation curve for dimensioning the pump necessary to pump the fluid flow I want.

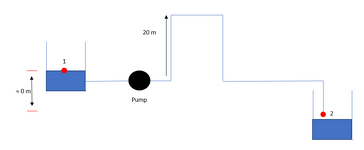

The system is as shown below, where practically the source and end tank would be at the same height, but in between, apart from the elbows, valves, etc., there is a 20 meters pipe up and then down (it has to cross a street over it).

If I apply Bernouilli in points 1-2 it will give me an ‘erroneous’ or incorrect value for my installation, as it will not take into account the 20 m of ascent pipe. My question is:

When calculating the head loss, only the friction losses are taken into account, either in pipes and fittings, but in this type of case, it would obviously be necessary to add the manometric height that has to be saved by that vertical pipe, right?

And now... the height of 20 metres that I have to save, wouldn't the downward section give me "free energy" to me later? because there I would have that manometric height that makes me ‘gain’ pressure for the descent, wouldn't it?

In this particular case, it is difficult for me to interpret the system in order to get the curve of the installation.

Thank you very much in advance for your comments

Regards,

I have a doubt about the calculation of the installation curve for dimensioning the pump necessary to pump the fluid flow I want.

The system is as shown below, where practically the source and end tank would be at the same height, but in between, apart from the elbows, valves, etc., there is a 20 meters pipe up and then down (it has to cross a street over it).

If I apply Bernouilli in points 1-2 it will give me an ‘erroneous’ or incorrect value for my installation, as it will not take into account the 20 m of ascent pipe. My question is:

When calculating the head loss, only the friction losses are taken into account, either in pipes and fittings, but in this type of case, it would obviously be necessary to add the manometric height that has to be saved by that vertical pipe, right?

And now... the height of 20 metres that I have to save, wouldn't the downward section give me "free energy" to me later? because there I would have that manometric height that makes me ‘gain’ pressure for the descent, wouldn't it?

In this particular case, it is difficult for me to interpret the system in order to get the curve of the installation.

Thank you very much in advance for your comments

Regards,