Hi everyone,

I'm currently working on a high-rise concrete residential tower in Canada, and I'd like to hear your insights on flat slab curing in cold weather.

The structure is being built through the winter at higher floors (20+), and we've noticed that the slabs aren’t receiving any curing. Flying forms are being stripped 24–48 hours after the pour, and heating is applied from the floor below. That means there’s no curing on either face of the slab, and no insulating blankets on top, since the workers are already on that floor the next day.

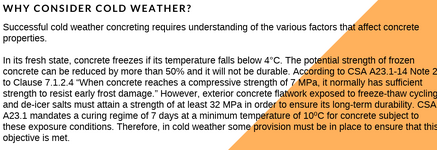

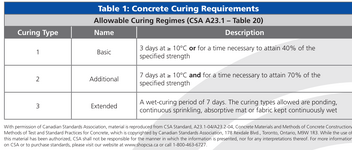

The contractor claims that all high-rise projects in the area follow the same approach, as there’s no curing compound that works effectively in cold temperatures, meaning proper curing would require pausing work for a few days at each level.

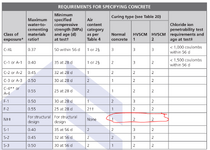

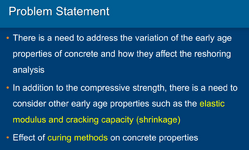

We’re concerned about the potential impact of this on durability and deflections (2-way slabs, 215mm thick, 6m spans). While I know this lack of curing isn’t compliant with the code, nor ideal, is it really a significant issue? Is skipping curing really common and accepted practice in cold weather high-rise construction?

Side note : This is my first post here, but I’ve read hundreds of discussions on this forum over the years and have learned so much. Huge thanks to everyone who shares their knowledge! And a special shoutout to KootK! You’re a legend in my office!

I'm currently working on a high-rise concrete residential tower in Canada, and I'd like to hear your insights on flat slab curing in cold weather.

The structure is being built through the winter at higher floors (20+), and we've noticed that the slabs aren’t receiving any curing. Flying forms are being stripped 24–48 hours after the pour, and heating is applied from the floor below. That means there’s no curing on either face of the slab, and no insulating blankets on top, since the workers are already on that floor the next day.

The contractor claims that all high-rise projects in the area follow the same approach, as there’s no curing compound that works effectively in cold temperatures, meaning proper curing would require pausing work for a few days at each level.

We’re concerned about the potential impact of this on durability and deflections (2-way slabs, 215mm thick, 6m spans). While I know this lack of curing isn’t compliant with the code, nor ideal, is it really a significant issue? Is skipping curing really common and accepted practice in cold weather high-rise construction?

Side note : This is my first post here, but I’ve read hundreds of discussions on this forum over the years and have learned so much. Huge thanks to everyone who shares their knowledge! And a special shoutout to KootK! You’re a legend in my office!

Last edited: