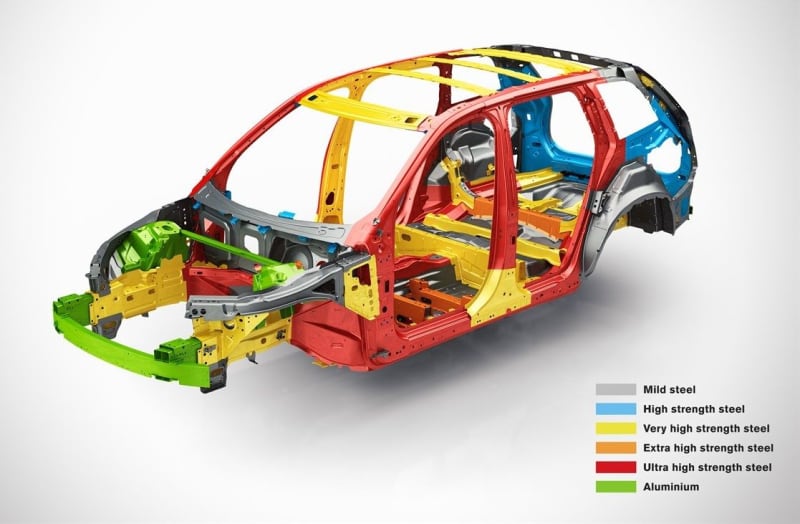

Just saw the above image on LinkedIn.

As a welding engineer, I'm wondering:

1) is it correct, that the fromt suspension turrets are in aluminium, (cast/deep drawn?)

and if so,

2) how are they connected to the steel frame (conventional welding isn't an option, that leaves deformation joining, fastening using bolts or rivets, adhesives, ...) ?

I'd say these are fairly high (cyclic) loaded parts, so aluminium seems not logical, but on the other hand I have zero experience in car frame, unibody or chassis design, so there's that if this is a stupid question...

![[peace] [peace] [peace]](/data/assets/smilies/peace.gif)