Rocket_Science

Mechanical

- Mar 25, 2025

- 3

Hi, I am a mechanical engineering student and I wanted to ask some questions about design of mechanical parts so that they don't break, because I tried putting together all I learned so far and I noticed I have some gaps that apparently they didn't cover in my uni courses.

I think I already have a good grasp on how to design parts (made out of a ductile material such as steel) so that they do not yield due to a static load. The process is theoretically simple, you just have to make sure that for each point of the part you are considering, the Von Mises stress doesn't get bigger than the material yield strength. The part could be complex and the stresses inside could be difficult to determine, but in the end it all reduces to checking the VM equivalent stress.

My doubts are specifically about the breaking condition of a part, because so far they only taught me to design parts so that they don't yield. At university we only saw simple cases of breaking due to uniaxial tension and the net stress simply had to be less than the UTS of the material. In practice it is not always possible to prevent local yielding (as in small fillets, or where there are contact stresses) so usually you calculate the average stress and compare that to the UTS of the part in simple cases.

My understanding so far is that when a part is designed against breaking, you can no longer use a local failure criterion like Von Mises because stress redistribution happens and elastic stresses become kind of meaningless (or are there local failure criterions that work for this purpose?) so it is easier to use a non local criterion such as choosing a surface where you think the part will break and calculating the mean stresses there.

I chose some examples relative to bolted joints to better expose my doubts, not because my doubts are relative to bolted joints specifically, but because it is where I most often saw these kinds of problems appear.

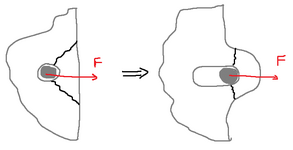

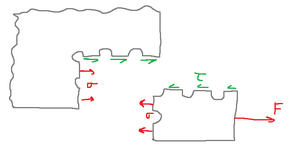

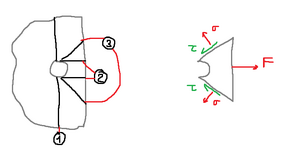

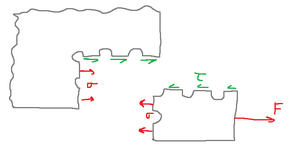

1) If we consider a bolt placed near an edge, to prevent tear out we check the mean stresses on the surfaces on the drawing:

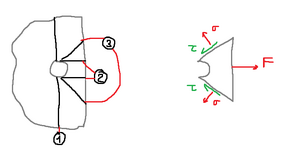

For surface 1 and 2 it is easy to determine if the part will break because the stresses will be only tension (1) or only shear (2). When it comes to surface 3 however it becomes more difficult to understand if the part will break, because after I find the shear and normal stresses on the surface, how do I understand if their current combination will result in breaking of the part? Again, I never heard of breaking criteria for ductile materials, only yield criteria, so I have no idea if the part will break along that surface or not.

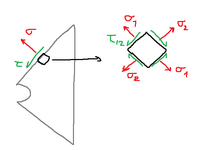

2) Taking the same example as above, if I think about it even more, I then notice that I am also forgetting that the small material elements near the surface are also loaded by stresses in their surface perpendicular to the selected surface:

How do these stresses affect the breaking of the part? Do they even affect it? I ask because I don't remember ever considering them when doing these kinds of verifications, but in principle one should not forget them.

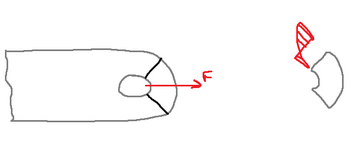

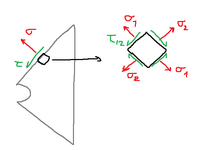

3) When I have the scenario shown in the drawing below, how can I determine how much of the force will be acting as shear and how much will be acting as normal stress?

To verify that this kind of failure doesn't happen, I can just make sure that neither of the mean stresses on the two surfaces is bigger than the ultimate tensile/shear stress of the material. The difficulty is understanding how the load divides itself here. To add to this I also don't remember having ever seen the ultimate shear stress of a metal being tabulated somewhere, and I am quite sure it cannot be found from the UTS by using a yield criterion because that would indeed be for yielding stresses only.

I apologize if the topics here look like a mess, but I feel like I am missing something to connect the dots, because again we have never really gotten in depth in the breaking of a ductile part, only on the yielding. These are questions I have since a few weeks and I checked various books, some about classical strength of materials and some that went deep into theory of plasticity, but they were heavy in math and these problems commonly seem to be solved without having to use such complicated topics, so I wanted to be sure I needed them before studying them.

I think I already have a good grasp on how to design parts (made out of a ductile material such as steel) so that they do not yield due to a static load. The process is theoretically simple, you just have to make sure that for each point of the part you are considering, the Von Mises stress doesn't get bigger than the material yield strength. The part could be complex and the stresses inside could be difficult to determine, but in the end it all reduces to checking the VM equivalent stress.

My doubts are specifically about the breaking condition of a part, because so far they only taught me to design parts so that they don't yield. At university we only saw simple cases of breaking due to uniaxial tension and the net stress simply had to be less than the UTS of the material. In practice it is not always possible to prevent local yielding (as in small fillets, or where there are contact stresses) so usually you calculate the average stress and compare that to the UTS of the part in simple cases.

My understanding so far is that when a part is designed against breaking, you can no longer use a local failure criterion like Von Mises because stress redistribution happens and elastic stresses become kind of meaningless (or are there local failure criterions that work for this purpose?) so it is easier to use a non local criterion such as choosing a surface where you think the part will break and calculating the mean stresses there.

I chose some examples relative to bolted joints to better expose my doubts, not because my doubts are relative to bolted joints specifically, but because it is where I most often saw these kinds of problems appear.

1) If we consider a bolt placed near an edge, to prevent tear out we check the mean stresses on the surfaces on the drawing:

For surface 1 and 2 it is easy to determine if the part will break because the stresses will be only tension (1) or only shear (2). When it comes to surface 3 however it becomes more difficult to understand if the part will break, because after I find the shear and normal stresses on the surface, how do I understand if their current combination will result in breaking of the part? Again, I never heard of breaking criteria for ductile materials, only yield criteria, so I have no idea if the part will break along that surface or not.

2) Taking the same example as above, if I think about it even more, I then notice that I am also forgetting that the small material elements near the surface are also loaded by stresses in their surface perpendicular to the selected surface:

How do these stresses affect the breaking of the part? Do they even affect it? I ask because I don't remember ever considering them when doing these kinds of verifications, but in principle one should not forget them.

3) When I have the scenario shown in the drawing below, how can I determine how much of the force will be acting as shear and how much will be acting as normal stress?

To verify that this kind of failure doesn't happen, I can just make sure that neither of the mean stresses on the two surfaces is bigger than the ultimate tensile/shear stress of the material. The difficulty is understanding how the load divides itself here. To add to this I also don't remember having ever seen the ultimate shear stress of a metal being tabulated somewhere, and I am quite sure it cannot be found from the UTS by using a yield criterion because that would indeed be for yielding stresses only.

I apologize if the topics here look like a mess, but I feel like I am missing something to connect the dots, because again we have never really gotten in depth in the breaking of a ductile part, only on the yielding. These are questions I have since a few weeks and I checked various books, some about classical strength of materials and some that went deep into theory of plasticity, but they were heavy in math and these problems commonly seem to be solved without having to use such complicated topics, so I wanted to be sure I needed them before studying them.