Lomarandil

Structural

So, I thought I had a grasp on this -- but recent questions from a colleague have me wondering again.

The base of the question is when do warping normal and shear stresses develop in an open cross-section beam with torsion? For the sake of simplicity, let's consider only simply supported beams.

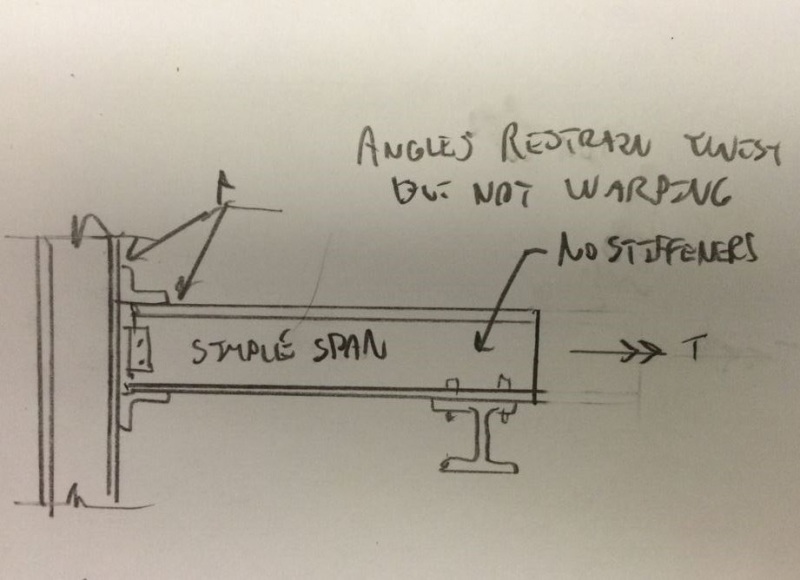

AISC Design Guide 9 goes to great lengths (p. 3, 11, 12, 14, etc) to express that when a member is allowed to warp freely, warping stresses do not develop. I've taken this "warping freely" primarily to be in the absence of fixed-style flange end connections, flange stiffeners or added webs at the flange tips, kickers, etc. (See WillisV response in

But then, in the design examples and torsional functions, members that are flexurally and torsionally pinned (presumably a simple shear tab connection) are shown to develop Θ" and therefore warping normal stresses along the length of the members.

The best explanation I can think of is that the rate of change of twist itself is restraining each cross-sectional slice of a beam with respect to the adjacent slices. But if this is the case, and I'd imagine it would be the case in nearly every structural application, why would AISC even discuss a mythical "freely warping" beam?

What am I missing here? Thanks!

The base of the question is when do warping normal and shear stresses develop in an open cross-section beam with torsion? For the sake of simplicity, let's consider only simply supported beams.

AISC Design Guide 9 goes to great lengths (p. 3, 11, 12, 14, etc) to express that when a member is allowed to warp freely, warping stresses do not develop. I've taken this "warping freely" primarily to be in the absence of fixed-style flange end connections, flange stiffeners or added webs at the flange tips, kickers, etc. (See WillisV response in

But then, in the design examples and torsional functions, members that are flexurally and torsionally pinned (presumably a simple shear tab connection) are shown to develop Θ" and therefore warping normal stresses along the length of the members.

The best explanation I can think of is that the rate of change of twist itself is restraining each cross-sectional slice of a beam with respect to the adjacent slices. But if this is the case, and I'd imagine it would be the case in nearly every structural application, why would AISC even discuss a mythical "freely warping" beam?

What am I missing here? Thanks!