-

6

- #1

JohnRBaker

Mechanical

- Jun 1, 2006

- 37,096

I wanted to post this earlier today (Monday) but it's been one of those days.

45 Years ago today, I sat down in front of a Unigraphics (the forerunner of NX) terminal for the first time. The company I was working for at the time, back in Michigan, had just purchased a three-terminal UG system and six employees were sent out to Carson, CA, for a week of training.

This is what the world headquarters of the United Computing Corporation, which was housed in an old US Post Office building in Carson, CA. This was where we came to take our training class:

I represented the mechanical design department of the Food Engineering division (we manufactured machinery for large commercial bakeries). We also had another engineer who represented the electrical department. There were two representatives from our Chemical Machinery Division, which we shared our factory and machines shop with, as well as two individuals from the Manufacturing Division, which supported both the Food and Chemical Divisions.

Our system was configured around a Data General S-230, 16-bit minicomputer, with 128Kb of memory (that's NOT a typo) and it had a 96Mb disk drive. Attached to this was three Tektronix DVST (Direct View Storage Tube) terminals (AKA 'Green Screens'), one UniApt station, a paper-tape punch and reader, a 9-track tape unit, a line printer, a teletype used as the system counsel, a Xerox hardcopy unit and a 960 Calcomp plotter. The entire system, hardware and software, cost $400,000 (and that was 1977 dollars), basically $100k per seat (3 UG and 1 UniApt).

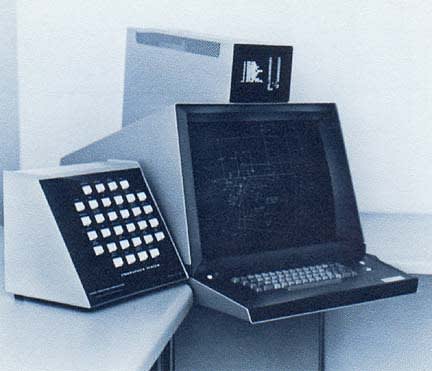

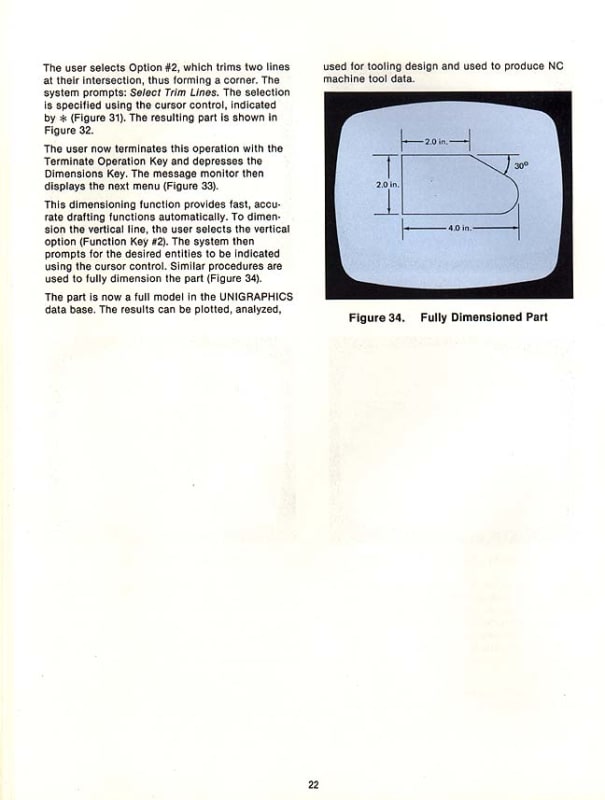

And for those wondering what a UG terminal look like back then, this was what we were trained on and what we used everyday to do our work:

There was no mouse to move the cursor, you used the two thumb-wheels that you see at the far right-hand side of the keyboard, one to control the horizontal and one to control the vertical movement of the onscreen cursor. The button box on the left, known as a PFK (Program Function Keyboard) was used to select menu options which were displayed on the small screen located above the main working screen.

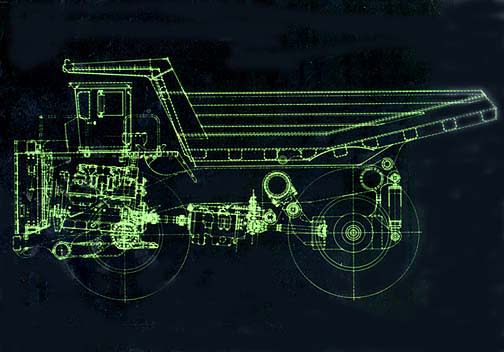

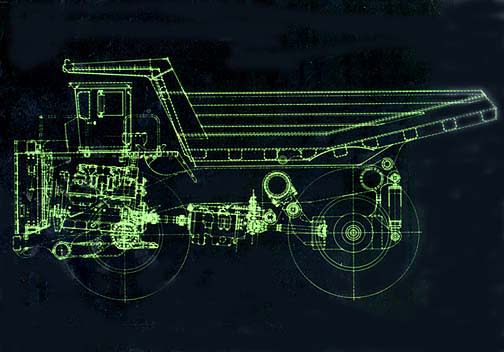

Speaking of 'Green Screens', this is what a typical display would look like:

And BTW, if you decided you wanted to delete something, you had to select the 'Delete' function from the PFK, select the item on the screen which would show a small 'o' to indicate that it had been selected and then after you hit 'Entry Complete' the small 'o' was replace with a small 'x' to indicate that it had been deleted. Note that you could still SEE the object that you just deleted, but if you wanted to have it go away, you had to hit the 'Repaint' button, which would first remove everything from the screen and then redraw ALL of the objects that had NOT been deleted. You could always spot a new user as he would do a 'Repaint' after every deletion, but an old timer would work for four or five minutes, or even longer, before they would finally hit 'Repaint' since that operation could take a long time to complete, sometimes as much as 30 seconds or more.

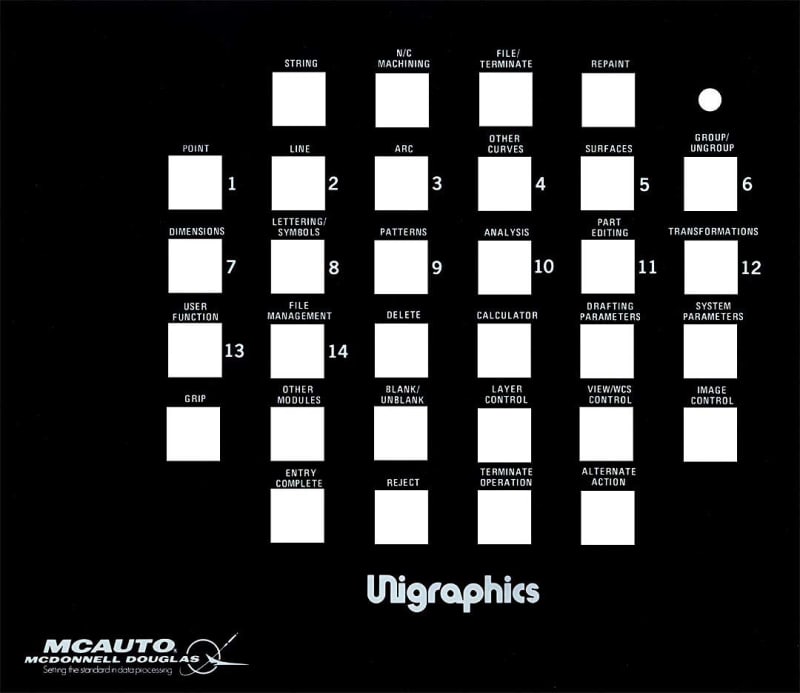

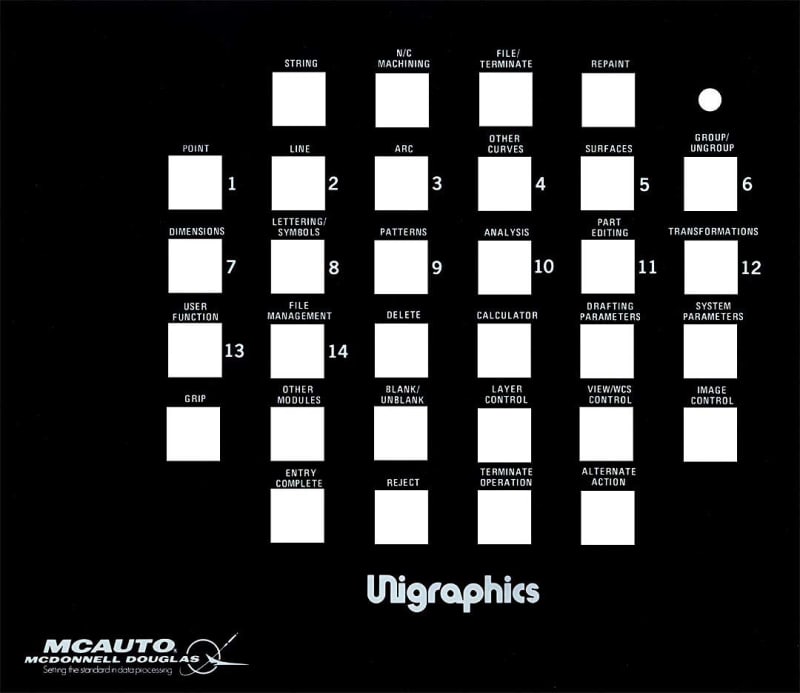

And for those who would like to know what the menu options were, here's a typical PFK overlay:

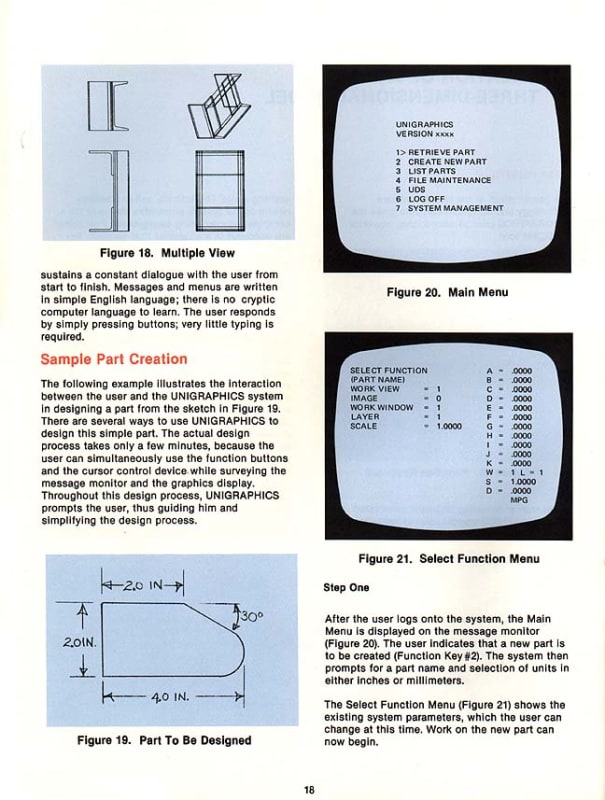

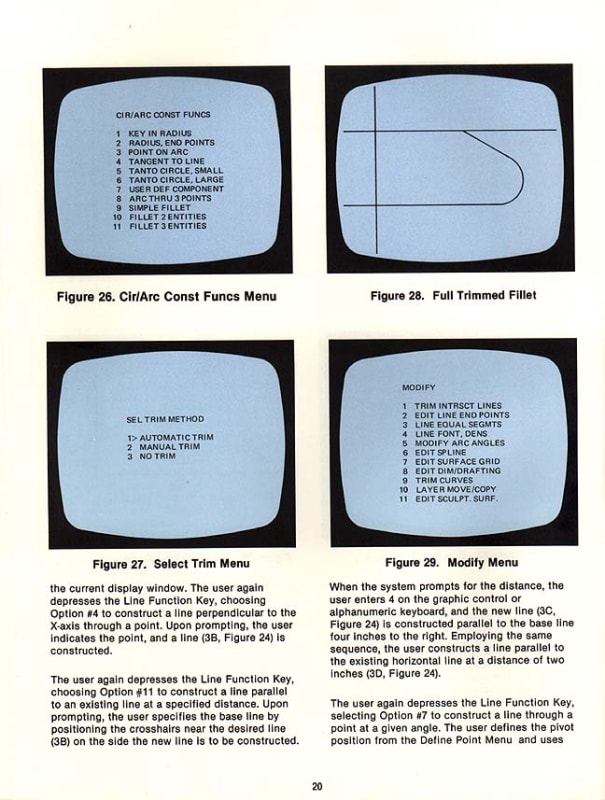

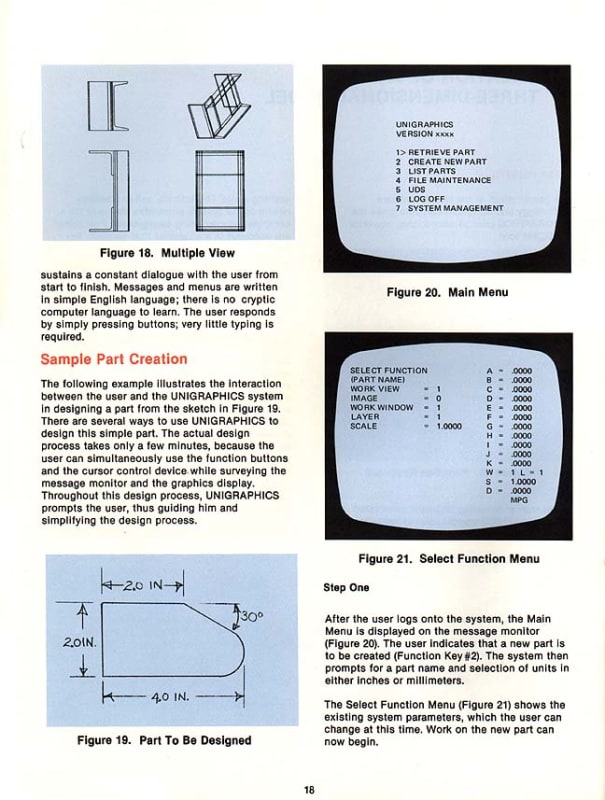

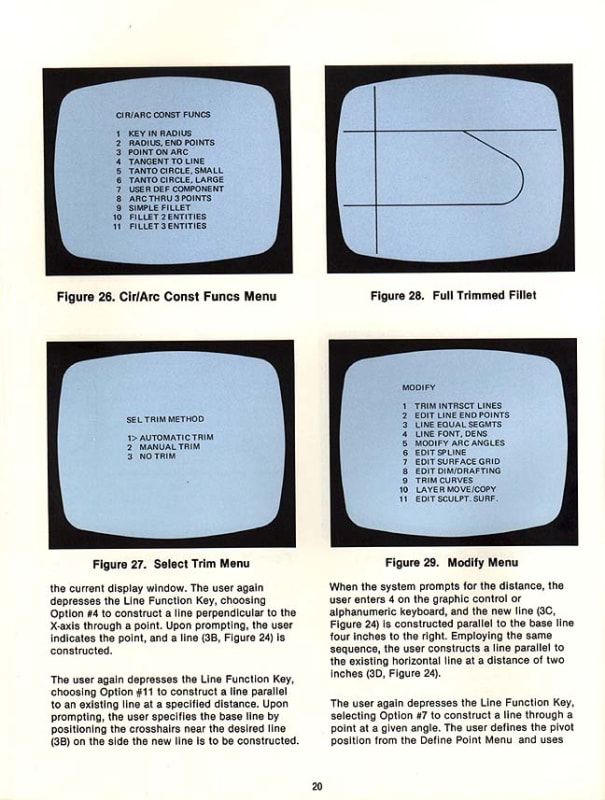

Note that each button was lighted and the lights would indicate which options were available for you to pick. Note that the 14 numbered buttons corresponded to the 14 sub-menus that would be displayed after you had selected a function on the PFK. To give you an idea what these menus looked like, here's a couple of pages from an early marketing brochure showing a simple exercise showing how you interacted with UG:

In the above image, the first screen (this was displayed in the small monitor above the main screen) is what you saw after the system had booted and you had logged in and were ready to either open up an existing Part file or start a new one. The second screen shows what was displayed before you selected a function on the PFK.

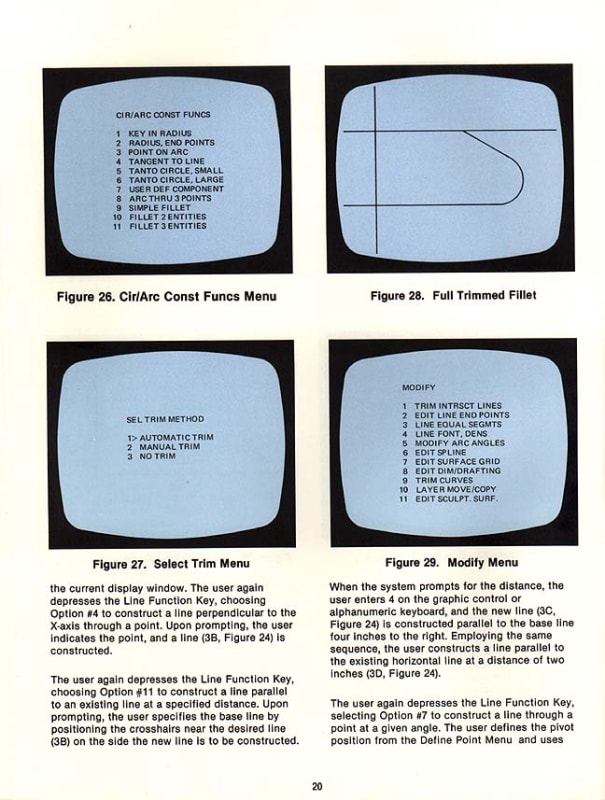

In this image you see what some of the sub-menus looked like after you had selected a main function. Note that the numbered menu option would have a corresponding button lite on the PFK so that you would know which button to push to get to the next sub-menu, which could be several layers deep.

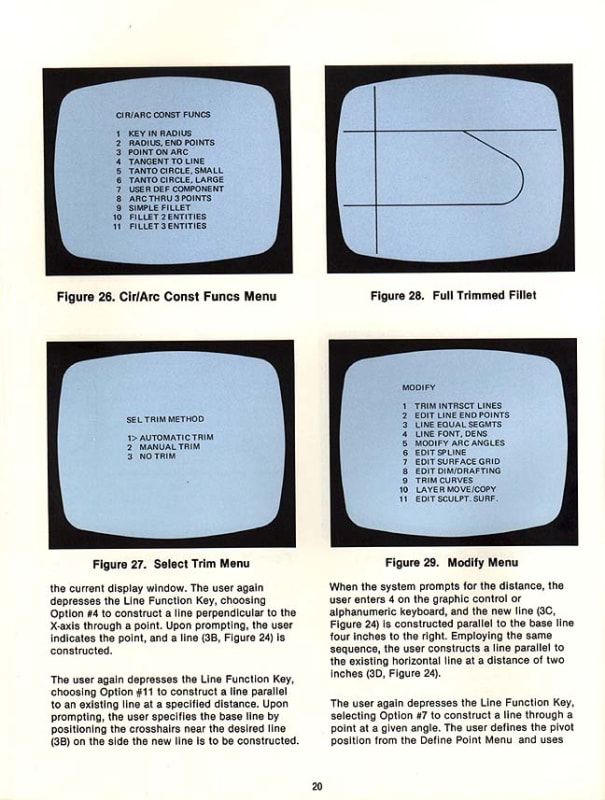

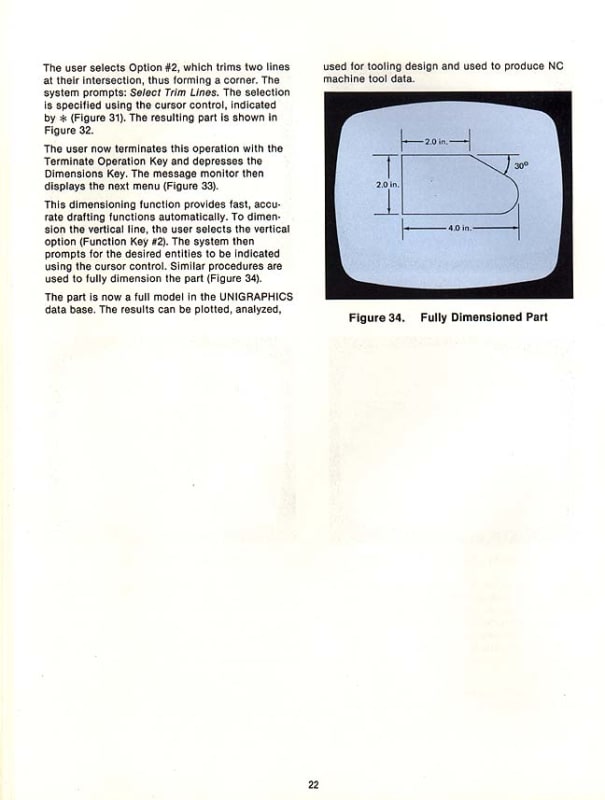

Here are a couple more pages to show you how you would complete the example in the brochure:

Now this might look complex and like you had to do a lot of button pushing and that there was a lot of wait time, but after awhile you got to know what the menus were going to ask and which buttons were what. And you would notice that you could 'type ahead' in the sense that you could go ahead and select the buttons which you knew were going do what you wanted. During our first training class, our instructor warned us not to type too far ahead as the buffer would only hold about 16 selections until the buffer was full and would stop accepting commands until it was empty. We thought the guy was crazy, who in the world could ever get more then 16 button pushes ahead of the system. Well, after we got back to work it only took some of us about a month before we started to hit those limits. After awhile you found that you could pace yourself so that you could type ahead and the system would keep-up with you pretty good. BTW, they later expanded the buffer, based on user requests, to about 30 keystrokes (BTW, the buffer included both PFK selections and keyboard entries).

If you would like to actually see how the system worked, the link below will take you to a marketing video which the United Computing Company was using about the time that our company bought their first system in 1977. The video is a bit over 15 minutes long and please excuse the quality as this was copied from a 16mm film. You'll spot how old the film is by the hair styles:

Note that after our one week Basic UG class they happened to be holding the SECOND annual Users Group Meeting in Long Beach at McDonnell Douglas (who had just purchased United Computing), and we were invited to stay for the meeting. Note that at the time there were only about 25 companies using UG and our company, Baker Perkins (no relation) was the first company to buy a second UG system. One of our sister companies in Peterborough, England, had purchased a UG system a few months before we did and they were first UG system installed outside of North America. They also sent a couple of people to the meeting, which was there first as well.

And before anyone asks what VERSION of the software were we using, well the first actual version of Unigraphics which had an actual release name was UGI R1. The R stood for restructured as it was first full rewrite of the Hanratty code (now there's a story for another day, about Dr Pat Hanratty, the TRUE father of CADCAM). That version wasn't released until 1978 so that meant that, even though it was never officially named this, that we were running UG0 (as in 'zero'). Now in those days your version was the date on the tape. United would sell a system and when they were ready to install it, they would cut a copy of whatever version of the software was running that day, and that would be your copy. And when I say tapes, this is how the software was delivered to us, on 9-track tapes:

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed my trip down memory lane. If anyone has their own story of how they were introduced to UG/NX, please, regal us.

And for the record, three years after United sold us our first UG system, I left Baker Perkins after 14 years working in their R&D department, took my vested pension, which I'm collecting still today, moved from Saginaw, MI, to SoCal and went to work for the Automation Division of McDonnell Douglas Corporation, who by then had closed United Computer and had merged the company and staff into McAuto. That was in 1980 and I remained with the company, through virtually dozens of name changes, new owners, etc, until I retired in 2016.

John R. Baker, P.E. (ret)

Irvine, CA

Siemens PLM:

UG/NX Museum:

The secret of life is not finding someone to live with

It's finding someone you can't live without

45 Years ago today, I sat down in front of a Unigraphics (the forerunner of NX) terminal for the first time. The company I was working for at the time, back in Michigan, had just purchased a three-terminal UG system and six employees were sent out to Carson, CA, for a week of training.

This is what the world headquarters of the United Computing Corporation, which was housed in an old US Post Office building in Carson, CA. This was where we came to take our training class:

I represented the mechanical design department of the Food Engineering division (we manufactured machinery for large commercial bakeries). We also had another engineer who represented the electrical department. There were two representatives from our Chemical Machinery Division, which we shared our factory and machines shop with, as well as two individuals from the Manufacturing Division, which supported both the Food and Chemical Divisions.

Our system was configured around a Data General S-230, 16-bit minicomputer, with 128Kb of memory (that's NOT a typo) and it had a 96Mb disk drive. Attached to this was three Tektronix DVST (Direct View Storage Tube) terminals (AKA 'Green Screens'), one UniApt station, a paper-tape punch and reader, a 9-track tape unit, a line printer, a teletype used as the system counsel, a Xerox hardcopy unit and a 960 Calcomp plotter. The entire system, hardware and software, cost $400,000 (and that was 1977 dollars), basically $100k per seat (3 UG and 1 UniApt).

And for those wondering what a UG terminal look like back then, this was what we were trained on and what we used everyday to do our work:

There was no mouse to move the cursor, you used the two thumb-wheels that you see at the far right-hand side of the keyboard, one to control the horizontal and one to control the vertical movement of the onscreen cursor. The button box on the left, known as a PFK (Program Function Keyboard) was used to select menu options which were displayed on the small screen located above the main working screen.

Speaking of 'Green Screens', this is what a typical display would look like:

And BTW, if you decided you wanted to delete something, you had to select the 'Delete' function from the PFK, select the item on the screen which would show a small 'o' to indicate that it had been selected and then after you hit 'Entry Complete' the small 'o' was replace with a small 'x' to indicate that it had been deleted. Note that you could still SEE the object that you just deleted, but if you wanted to have it go away, you had to hit the 'Repaint' button, which would first remove everything from the screen and then redraw ALL of the objects that had NOT been deleted. You could always spot a new user as he would do a 'Repaint' after every deletion, but an old timer would work for four or five minutes, or even longer, before they would finally hit 'Repaint' since that operation could take a long time to complete, sometimes as much as 30 seconds or more.

And for those who would like to know what the menu options were, here's a typical PFK overlay:

Note that each button was lighted and the lights would indicate which options were available for you to pick. Note that the 14 numbered buttons corresponded to the 14 sub-menus that would be displayed after you had selected a function on the PFK. To give you an idea what these menus looked like, here's a couple of pages from an early marketing brochure showing a simple exercise showing how you interacted with UG:

In the above image, the first screen (this was displayed in the small monitor above the main screen) is what you saw after the system had booted and you had logged in and were ready to either open up an existing Part file or start a new one. The second screen shows what was displayed before you selected a function on the PFK.

In this image you see what some of the sub-menus looked like after you had selected a main function. Note that the numbered menu option would have a corresponding button lite on the PFK so that you would know which button to push to get to the next sub-menu, which could be several layers deep.

Here are a couple more pages to show you how you would complete the example in the brochure:

Now this might look complex and like you had to do a lot of button pushing and that there was a lot of wait time, but after awhile you got to know what the menus were going to ask and which buttons were what. And you would notice that you could 'type ahead' in the sense that you could go ahead and select the buttons which you knew were going do what you wanted. During our first training class, our instructor warned us not to type too far ahead as the buffer would only hold about 16 selections until the buffer was full and would stop accepting commands until it was empty. We thought the guy was crazy, who in the world could ever get more then 16 button pushes ahead of the system. Well, after we got back to work it only took some of us about a month before we started to hit those limits. After awhile you found that you could pace yourself so that you could type ahead and the system would keep-up with you pretty good. BTW, they later expanded the buffer, based on user requests, to about 30 keystrokes (BTW, the buffer included both PFK selections and keyboard entries).

If you would like to actually see how the system worked, the link below will take you to a marketing video which the United Computing Company was using about the time that our company bought their first system in 1977. The video is a bit over 15 minutes long and please excuse the quality as this was copied from a 16mm film. You'll spot how old the film is by the hair styles:

Note that after our one week Basic UG class they happened to be holding the SECOND annual Users Group Meeting in Long Beach at McDonnell Douglas (who had just purchased United Computing), and we were invited to stay for the meeting. Note that at the time there were only about 25 companies using UG and our company, Baker Perkins (no relation) was the first company to buy a second UG system. One of our sister companies in Peterborough, England, had purchased a UG system a few months before we did and they were first UG system installed outside of North America. They also sent a couple of people to the meeting, which was there first as well.

And before anyone asks what VERSION of the software were we using, well the first actual version of Unigraphics which had an actual release name was UGI R1. The R stood for restructured as it was first full rewrite of the Hanratty code (now there's a story for another day, about Dr Pat Hanratty, the TRUE father of CADCAM). That version wasn't released until 1978 so that meant that, even though it was never officially named this, that we were running UG0 (as in 'zero'). Now in those days your version was the date on the tape. United would sell a system and when they were ready to install it, they would cut a copy of whatever version of the software was running that day, and that would be your copy. And when I say tapes, this is how the software was delivered to us, on 9-track tapes:

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed my trip down memory lane. If anyone has their own story of how they were introduced to UG/NX, please, regal us.

And for the record, three years after United sold us our first UG system, I left Baker Perkins after 14 years working in their R&D department, took my vested pension, which I'm collecting still today, moved from Saginaw, MI, to SoCal and went to work for the Automation Division of McDonnell Douglas Corporation, who by then had closed United Computer and had merged the company and staff into McAuto. That was in 1980 and I remained with the company, through virtually dozens of name changes, new owners, etc, until I retired in 2016.

John R. Baker, P.E. (ret)

Irvine, CA

Siemens PLM:

UG/NX Museum:

The secret of life is not finding someone to live with

It's finding someone you can't live without