MintJulep:

I thought you meant stresses caused by the welding, but now I think you might actually mean the stresses in the weld, or welds, due to the various loads. I can certainly imagine a situation like you are describing, but would need a lot more details to really comment more definitively. I would be surprised that you didn’t see any weld failures, weld cracking, parent metal cracking, etc. if you could see significant movement or deformation of the combined parts. Did you actually hear sounds ("sprang!", whatever) when things seemed to move/change/fail? If you had two stiff parts and had to really clamp them together for fit-up before welding, needing large clamping forces, then you were adding a whole new loading (set of stresses) to the welds for which they were not designed. And, those stresses along with the stresses from lifting and moving, or for which the welds were originally designed could combine for some yielding or problems. But, we do this kind of fit-up clamping, etc. every day, usually without problems when done judiciously. Many times we have to heat treat (stress relieve) a large/stiff weldment before we do any machining on it or it will move around during machining and we can’t hold tolerances. The machining relieves, removes, affects some of the locked-in stresses and this causes the weldment to keep change shape slightly.

Part of what’s happening with yield stresses caused by and around welds is that the yielded material is usually well confined by surrounding material so it can’t go anywhere and some yielding isn’t an instant failure mechanism, but it does induce a bunch of residual stresses to accomplish this. Steel can continue to work just fine after having yielded, as long as you can tolerate the strains/deformations caused by the yielding. You’ve undoubtedly seen this on a stress/strain curve for steel, or can find it in many Strength of Materials/Theory of Elasticity texts. The stress at a point (or small volume) climbs the elastic part of the curve, starts to yield, and moves out on the plastic part of the curve; then when unloaded the stress moves down (maybe back to zero) from ‘this higher stress point’ essentially at the same slope as elastic part of the curve, but at a new strain. Reloading (restressing) causes a climb up this new slope line to ‘this higher stress point’ again, and if the loading continues the stress will move further out on the plastic part of the curve, and the cycle will/can repeat.

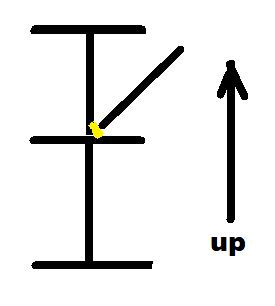

In my earlier example, a WT made from a flange and a web, and then made into a WF by adding a second flg., in each cycle of welding the two fillets, web to flg., the welds want to shrink/shorten as they cool, and the only way that can happen is for the member to take a curved shape (circular curve) with the weld line being a shorter circumferential arc than the free edge of the web, in the first case. Assuming I’ve welded the web to the flg. downhand, the WT will camber up, lifting the center of the WT up off the table because of this curvature change. This whole process leaves residual stresses, is held in equilibrium by these residual stresses. Now, in the second case, the WT added to another flg., again welding downhand, the same thing happens, but the WT is much stiffer than the web alone was, so the curvature due to the new welds cooling and shortening is less. To make the final WF straight, I would put the second flg. on the table with several graduated shims under it, max. shim thk. at center. Then, I’d press the WT down to fit the new flg. partly straightening it out, and the second fillet welding cycle would do the rest of the straightening. My beam is not very stiff over its length, so the pressing forces are not too great, as they are ultimately reacted by the new welds. Otherwise, this is not unlike you having clamped your parts together to weld them. But, your parts must have been much stiffer, thus needing much greater clamping forces.

The OP’ers. beam is all steel and the CTE is essentially a constant (.0000065 “/”/°F) for the base matr’l. and the weld deposits, so the temp. change (Texas to Alaska) would not cause deformation or curvature change. It would just cause a fairly uniform length change of the whole part as a function of the temp. change. We just don’t know enough about his built-up beam to make a judgement about what happened. I suspect it didn’t leave Texas as straight as he is being told it was, and the faber doesn’t know what its shape was either, or is hiding what it was. Still, if the piece was put on a very flexible flatbed trailer, and blocked to the trailer bed, or put on a fairly stiff trailer and not blocked well, and then a bunch of load was put on top of it you could get some ‘vibratory stress relieving’ which could cause some shape movement.