Hello,

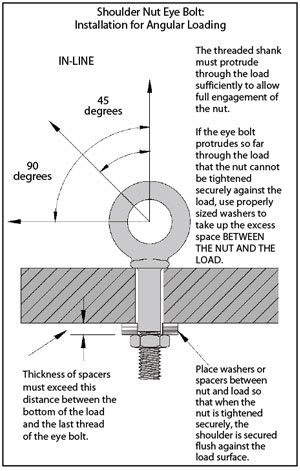

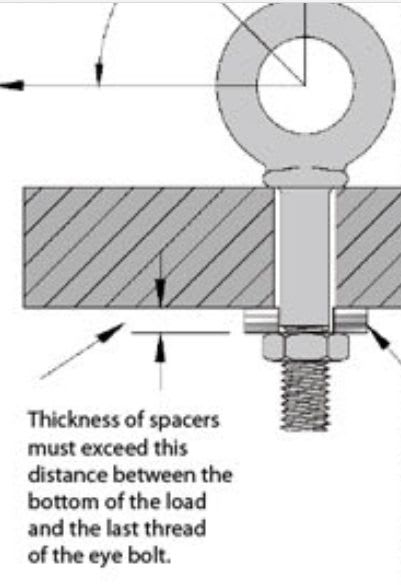

This is my first time specifying an eyebolt for lifting. Imagine a plate with a through hole. The eyebolt is inserted into the through hole on one side of the plate and is tightened with a nut on the other side of the plate. Given that we know the thread size and material of the eyebolt and nut, how do we go about determining the eyebolt's strength?

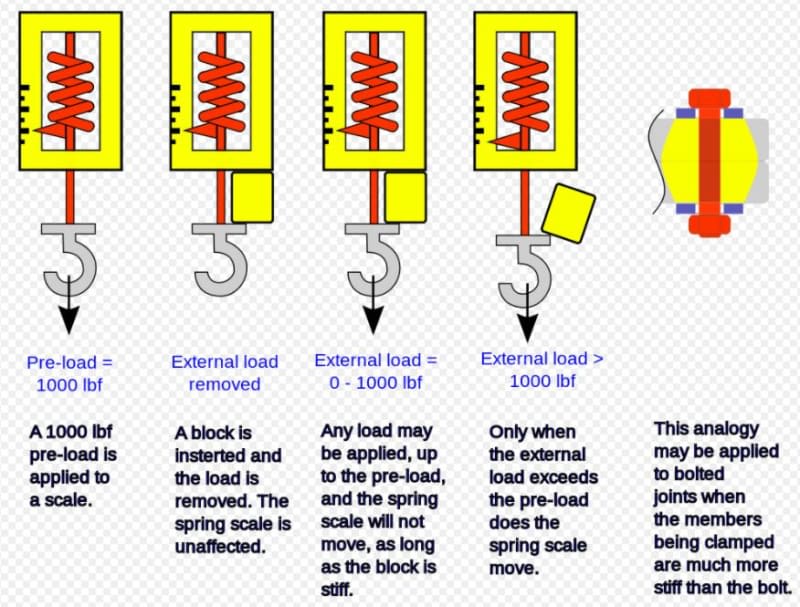

If you torque down the eyebolt, this develops a tension preload on it. It would appear to me that any lifting force on the eyebolt would then increase the tension in the eyebolt in addition to the initial preload. Is the strength of an eyebolt then determined by how large of a preload you initially develop?

This is my first time specifying an eyebolt for lifting. Imagine a plate with a through hole. The eyebolt is inserted into the through hole on one side of the plate and is tightened with a nut on the other side of the plate. Given that we know the thread size and material of the eyebolt and nut, how do we go about determining the eyebolt's strength?

If you torque down the eyebolt, this develops a tension preload on it. It would appear to me that any lifting force on the eyebolt would then increase the tension in the eyebolt in addition to the initial preload. Is the strength of an eyebolt then determined by how large of a preload you initially develop?