harrytos23

Student

- Nov 6, 2024

- 23

Hi everyone,

I tried searching more about this question but I'm getting different answers from different websites/forum. I might as well ask it here.

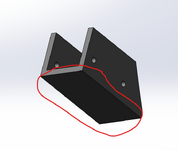

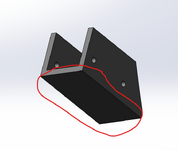

This piece of rubber is 4"x2.15", it's not much of surface area but better than nothing at all.

My question now is, is it really true that the contact patch/area will not have a different friction force than a single point of contact? Because many sources and people saying that the friction is not affected of the surface area of the contact point and just wanted to confirm that. And side question is, what formula should I use to calculate the friction force of it using the area as well? Thank you guys!!

I tried searching more about this question but I'm getting different answers from different websites/forum. I might as well ask it here.

This piece of rubber is 4"x2.15", it's not much of surface area but better than nothing at all.

My question now is, is it really true that the contact patch/area will not have a different friction force than a single point of contact? Because many sources and people saying that the friction is not affected of the surface area of the contact point and just wanted to confirm that. And side question is, what formula should I use to calculate the friction force of it using the area as well? Thank you guys!!