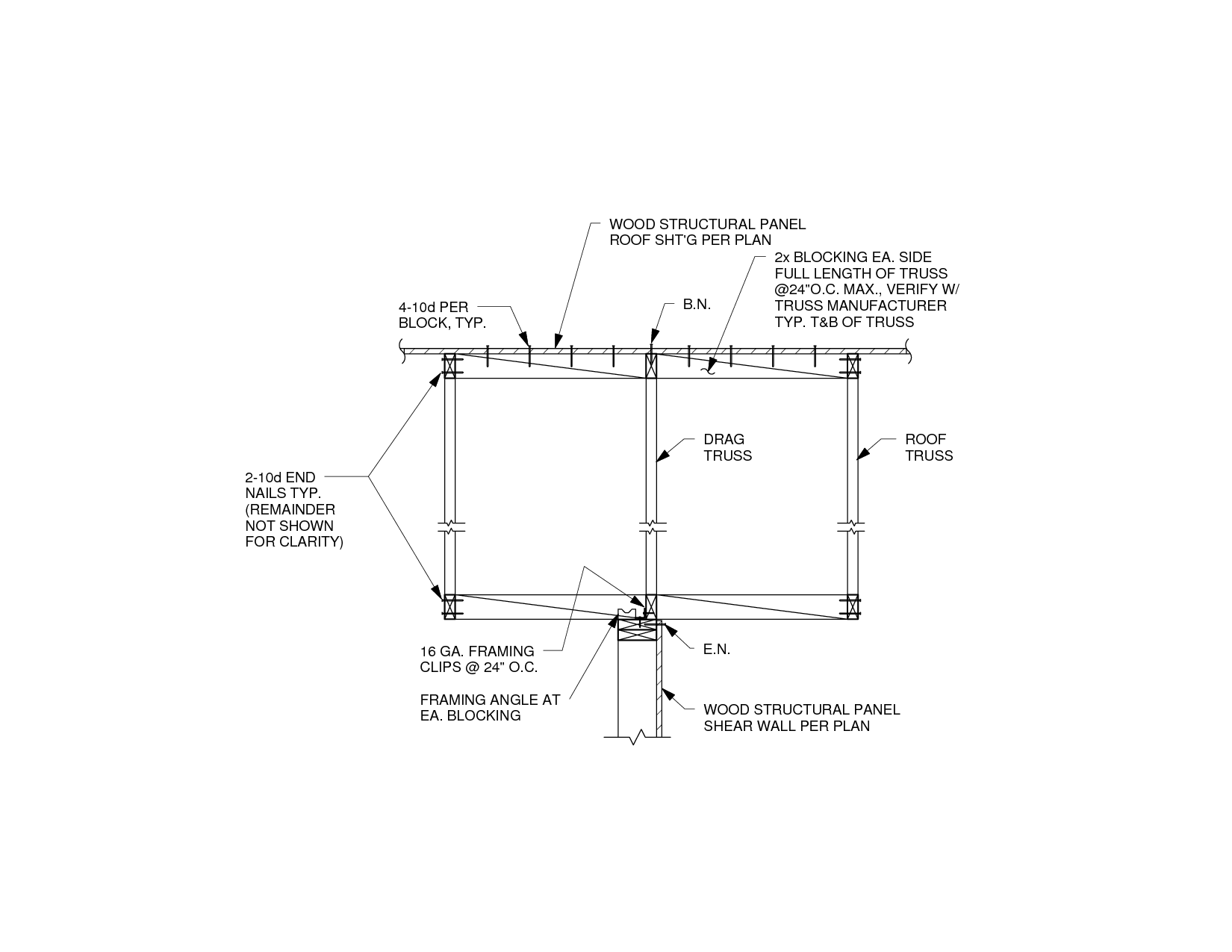

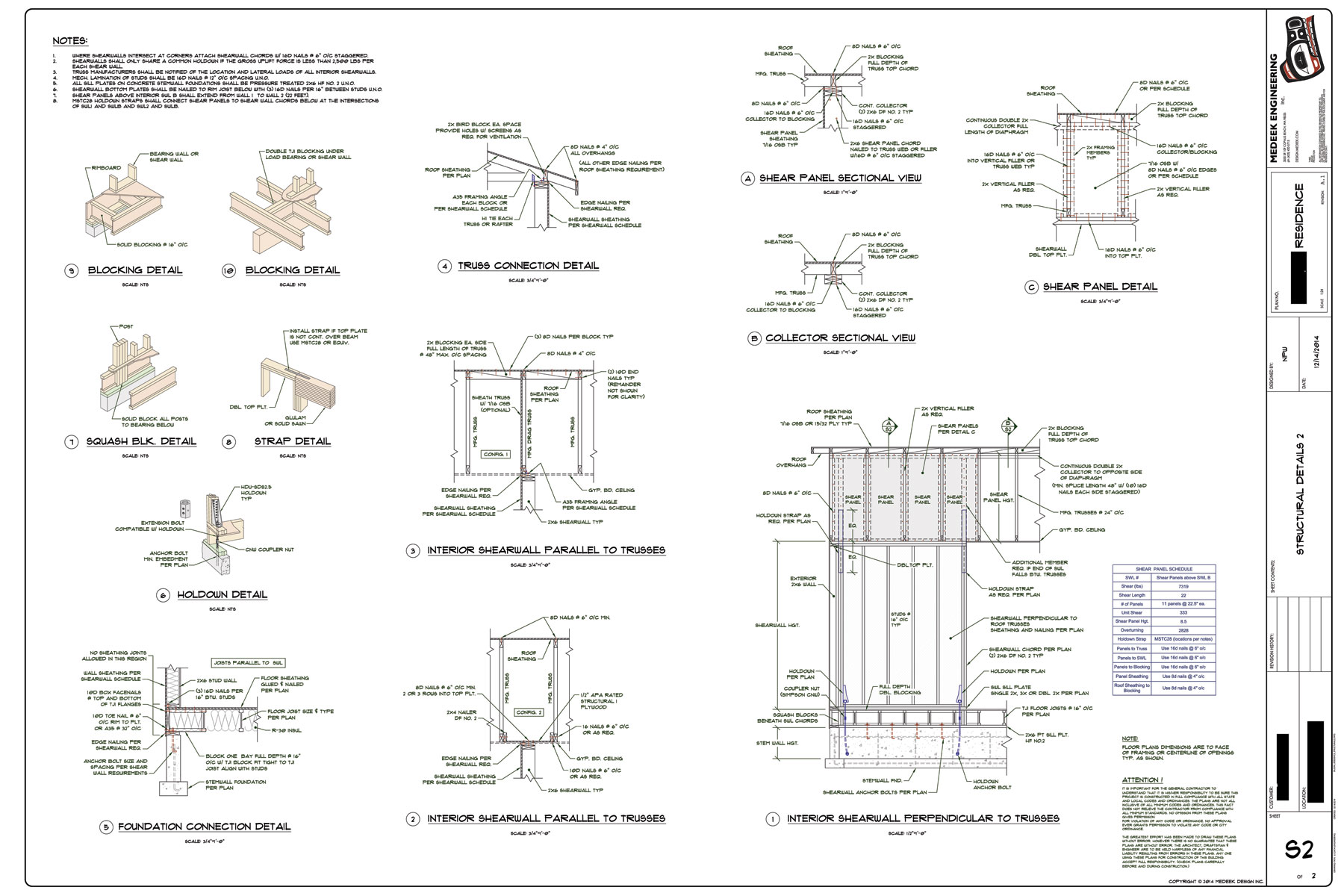

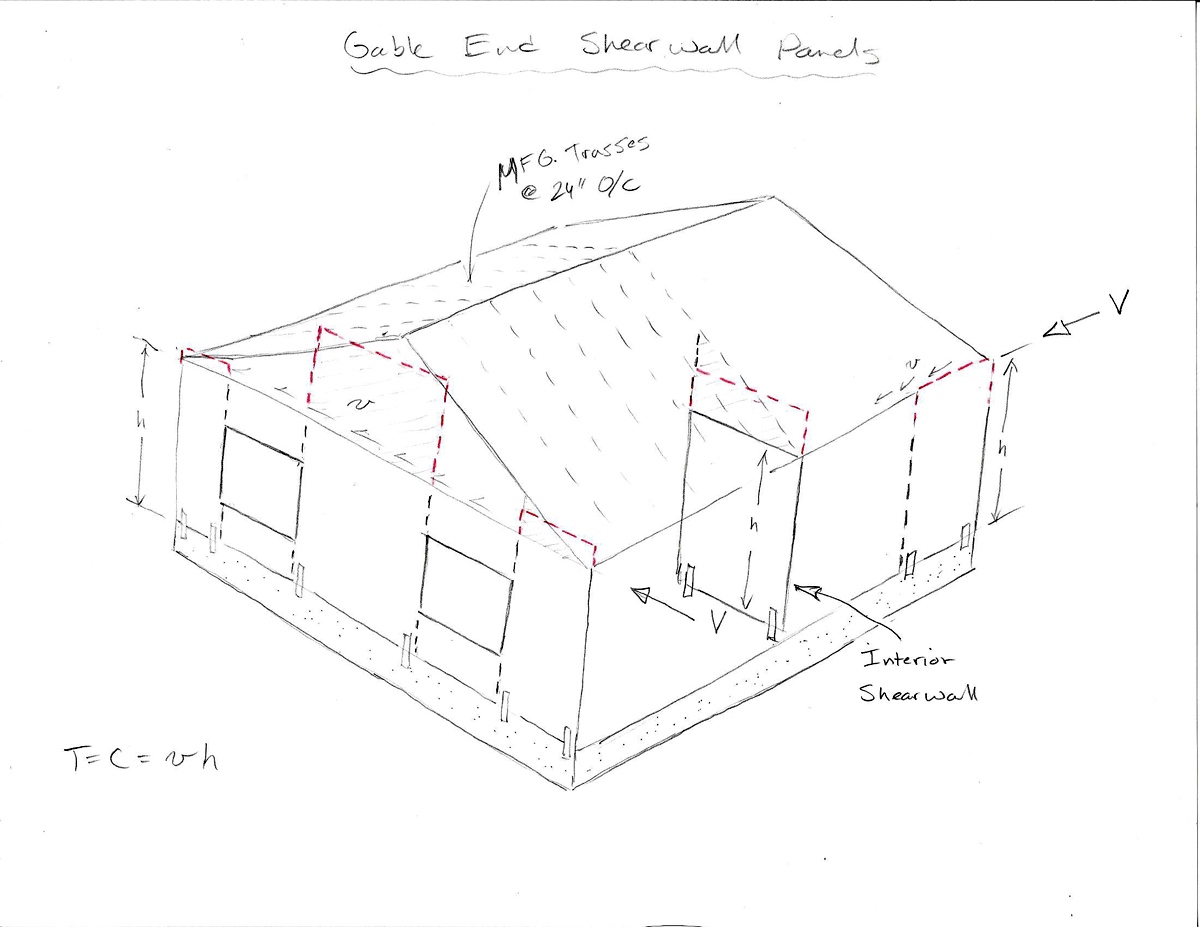

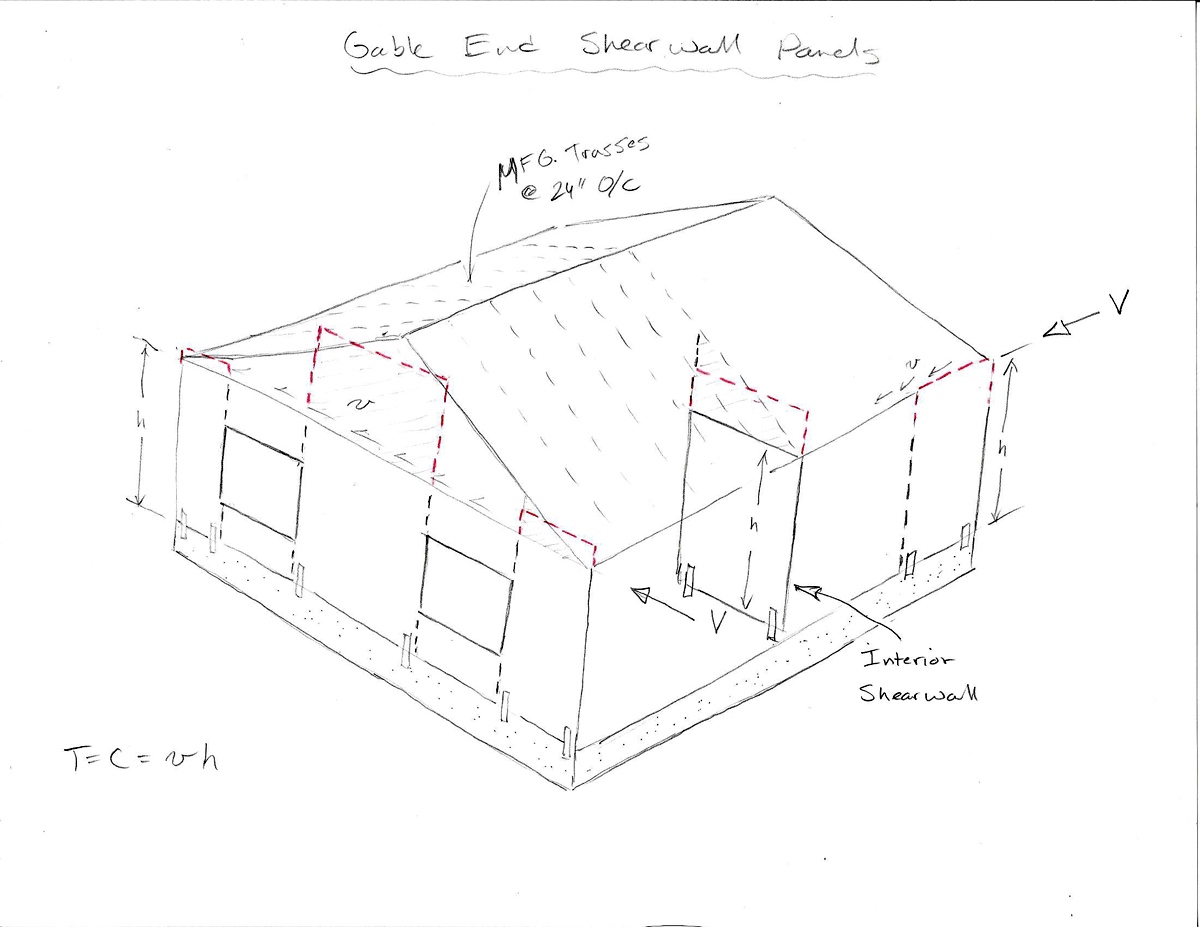

I've been mucking around with the Woodworks software and reading through some of its documentation. I noticed that the uplift forces being calculated for the holdowns was different than I was calculating manually for gable end shearwalls. Looking through the help files I noticed that the height being used to calculate the holdown force was not the wall height but actually the average height to the roof diaphragm for that segment (see diagram below):

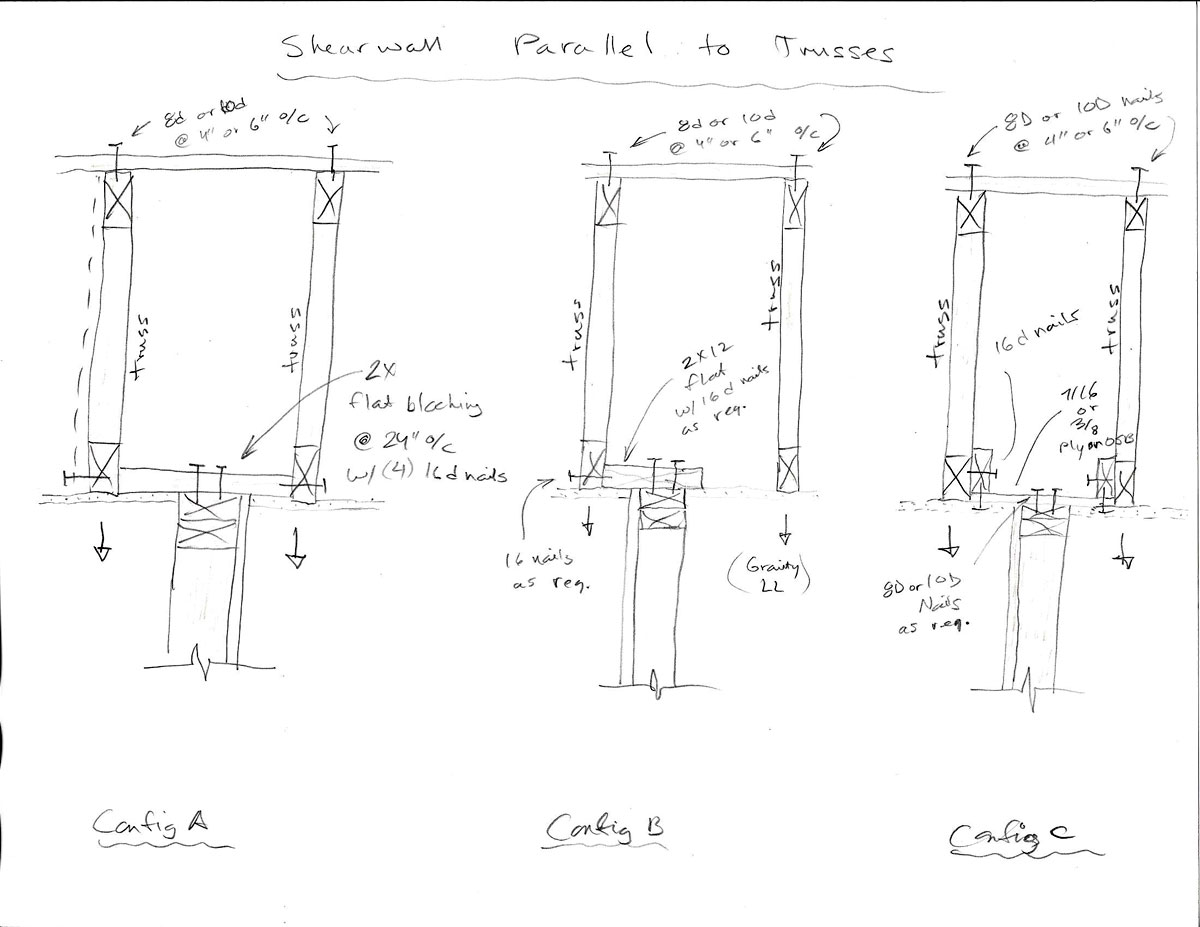

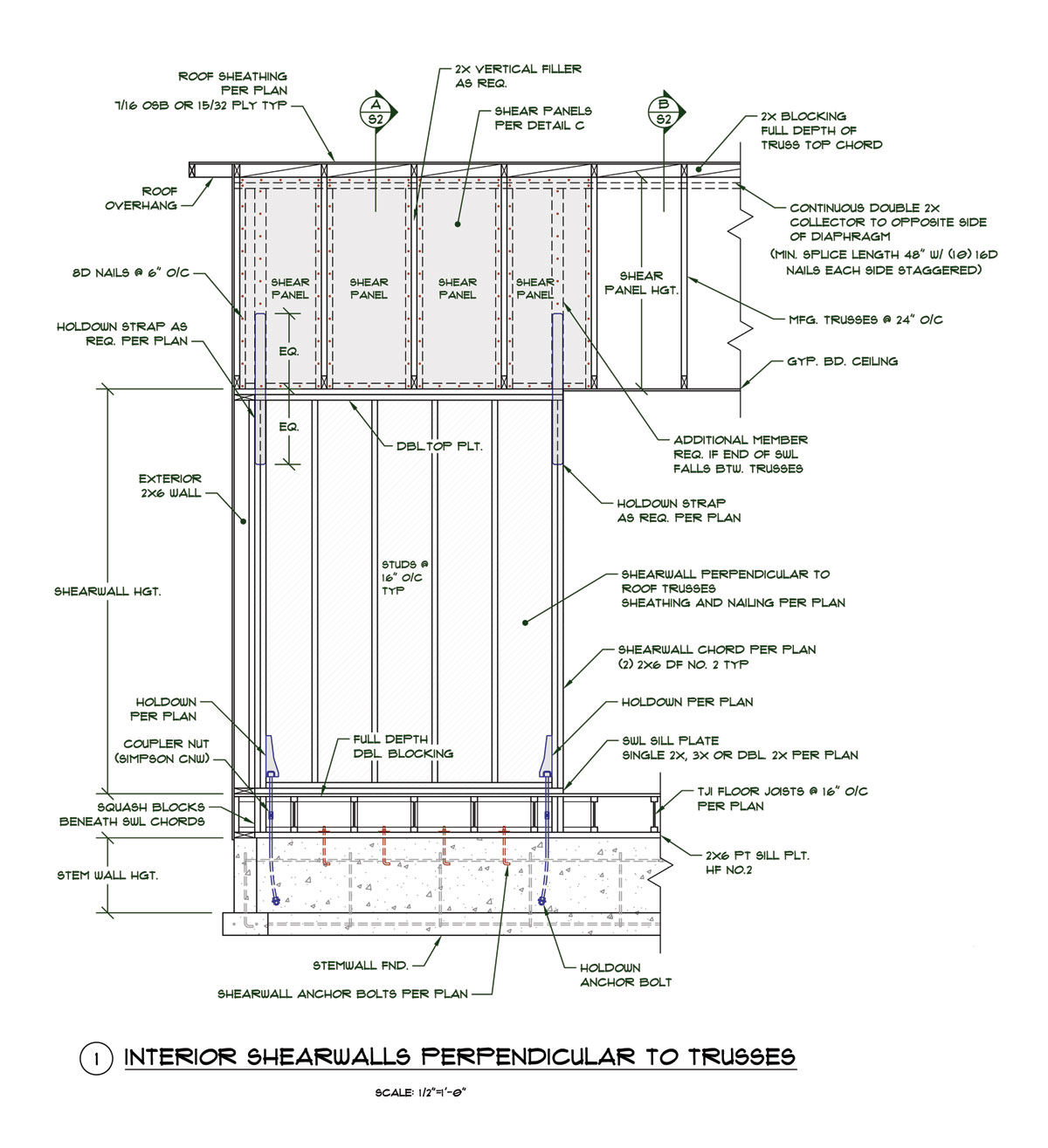

When a roof like the one shown above is composed of closely spaced trusses (max. 24" o/c) my thinking was they would act like mini shearwalls of their own and bring the diaphragm load down to the ceiling level where it would be transferred to the walls. I suppose the same argument can be made for interior shearwalls as shown above as well. However, I am now having to rethink this assumption.

The exterior shearwalls parallel to the ridge obviously are same height as the wall height but how is everyone else handling the gable end and interior shearwall heights?

A confused student is a good student.

When a roof like the one shown above is composed of closely spaced trusses (max. 24" o/c) my thinking was they would act like mini shearwalls of their own and bring the diaphragm load down to the ceiling level where it would be transferred to the walls. I suppose the same argument can be made for interior shearwalls as shown above as well. However, I am now having to rethink this assumption.

The exterior shearwalls parallel to the ridge obviously are same height as the wall height but how is everyone else handling the gable end and interior shearwall heights?

A confused student is a good student.