I am an EE, not an ME, so please accept my apology, (and point me to where it should be), if this is not the correct place to ask this question. I am a retired engineer looking to solve a 'personal' problem.

I have looked extensively for a solution to the below defined problem, and have found none. Let me save "you" time: I am well aware of the "64 to 74%" rules of thumb regarding packing density of spheres. Neither of those 'solutions' address my problem.

My problem defined is:

1) I have a cylinder whose dimensions (and therefore, volume), cannot be modified.

2) I need to add as much weight to that cylinder as I practically can using spheres of pure lead. (RhoPb = 11.34g/cc) (Price renders tungsten and gold "impractical".)

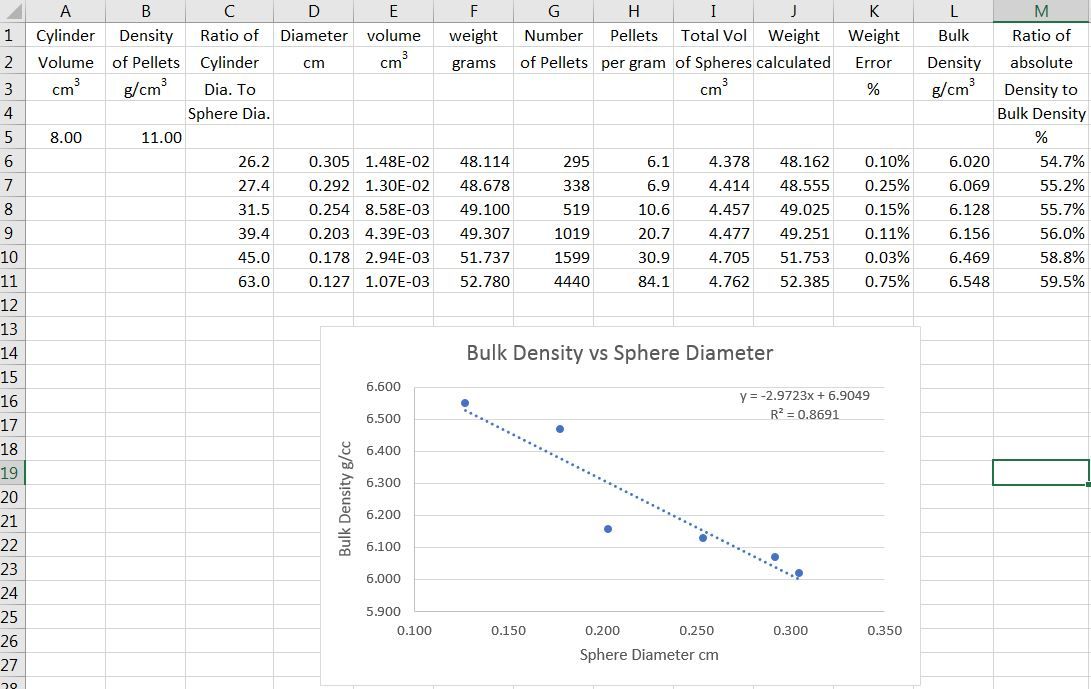

3) It is obvious that the smaller the sphere used, the higher the BULK density (weight) will be. However, there are practical reasons for not using spheres smaller than a given size. (At a point, spheres become "dust".)

4) The small-sphere handling issue does not have a threshold. Meaning that regardless of the starting sphere diameter, as sphere diameter gets smaller, the handling problems increase.

5) I want to maximize the weight of the cylinder, but I don't want to have to deal with the handling problems associated with "small" spheres. In other words; there is a point of diminishing returns where the gain realized in increased weight is offset by handling issues.

I want to be able to calculate BULK density in a CYLINDER as a function of sphere DIAMETER, when sphere density is known (and constant). The cylinder diameter and height are >> than the largest sphere diameter.

My problem restated in "simple" language is:

How does sphere diameter affect bulk density in a cylinder?

I have been to half a dozen "math" sites, and got NO help. Every time I have to talk to a mathematician I am reminded of why I am an Engineer.

Thanks!

Paul

I have looked extensively for a solution to the below defined problem, and have found none. Let me save "you" time: I am well aware of the "64 to 74%" rules of thumb regarding packing density of spheres. Neither of those 'solutions' address my problem.

My problem defined is:

1) I have a cylinder whose dimensions (and therefore, volume), cannot be modified.

2) I need to add as much weight to that cylinder as I practically can using spheres of pure lead. (RhoPb = 11.34g/cc) (Price renders tungsten and gold "impractical".)

3) It is obvious that the smaller the sphere used, the higher the BULK density (weight) will be. However, there are practical reasons for not using spheres smaller than a given size. (At a point, spheres become "dust".)

4) The small-sphere handling issue does not have a threshold. Meaning that regardless of the starting sphere diameter, as sphere diameter gets smaller, the handling problems increase.

5) I want to maximize the weight of the cylinder, but I don't want to have to deal with the handling problems associated with "small" spheres. In other words; there is a point of diminishing returns where the gain realized in increased weight is offset by handling issues.

I want to be able to calculate BULK density in a CYLINDER as a function of sphere DIAMETER, when sphere density is known (and constant). The cylinder diameter and height are >> than the largest sphere diameter.

My problem restated in "simple" language is:

How does sphere diameter affect bulk density in a cylinder?

I have been to half a dozen "math" sites, and got NO help. Every time I have to talk to a mathematician I am reminded of why I am an Engineer.

Thanks!

Paul