struct_eeyore

Structural

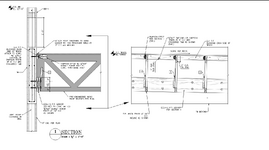

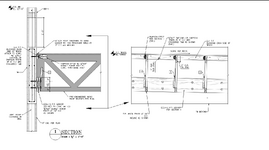

I've got a condition where I have to terminate flat roof wood trusses into a face of a parapeting (can I say that?) wall.

The bonus here is that the roof slopes, so in order to keep the sheathing flush with the top chords, I'm showing the trusses installed on an incline.

I've been mulling over the connection details and have come up with something like this (below)

Wondering if anyone will see any issue with what I'm proposing here - or any other comments/suggestions.

Thanks in advance.

The bonus here is that the roof slopes, so in order to keep the sheathing flush with the top chords, I'm showing the trusses installed on an incline.

I've been mulling over the connection details and have come up with something like this (below)

Wondering if anyone will see any issue with what I'm proposing here - or any other comments/suggestions.

Thanks in advance.