StructuEng

Structural

- Mar 4, 2025

- 4

Hello all.

Often the effective length of a column in steel frames is taken as the story height. This applies not only for flexural buckling, but also for lateral-torsional and pure torsional buckling.

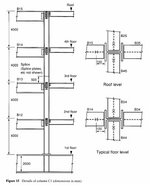

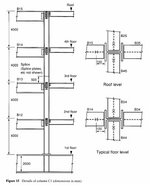

I'm currently reading the design guide "Worked examples for the design of steel structures" by Building Research Establishment, Steel Construction Institute and Ove Arup and partners. There is an example of how to calculate the lateral-torsional buckling resistance of a column in a steel frame. The illustration of one critical column in the frame is given as below:

Lateral-torsional buckling of the column is checked, because the eccentricity of the beam-column connection introduces bending moment in the column.

The authors continue to calculate the critical moment of the column assuming that the lateral-torsional buckling length of the column between levels is the story height (4 meters in this case). Per my understanding, buckling length for LTB is taken as the member length between torsionally braced points (sometimes called "fork" support). That is, the member should not be free to rotate between those points.

I'm curious, does this type of arrangement really provide full (or any) torsional restraint to the column at the story levels?

I wonder where the torsional support to the column comes from at all. The fin plate connection in the worked example surely does not provide a moment connection to the beam. I set out to do a small FEM calculation to study the rotational restraint provided by beams to the column in a similar situation.

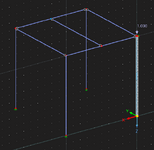

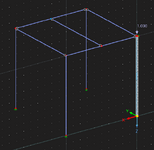

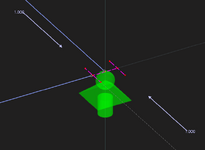

The frame dimensions are 10m x 10m x 10m. All profiles are HEA200, with S355 steel having E = 210 GPa. Bracing of the frame is hidden for clarity.

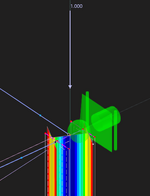

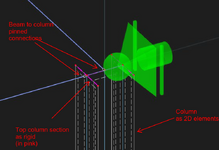

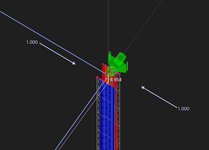

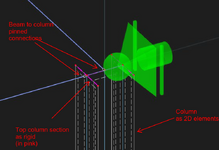

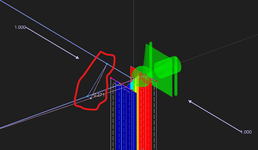

The column studied is the rightmost one in the picture above. In detail, it looks as follows:

One beam is connected directly to the column web. The other is connected to the column flange. The section where the beams connect to the column is considered rigid. This section is supported in XY plane, without any Z-direction or rotational restraint. The beams are connected with pin conditions to the column around both X and Y axis.

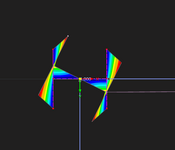

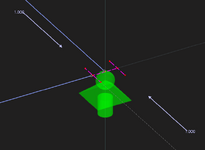

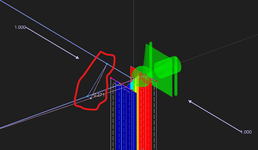

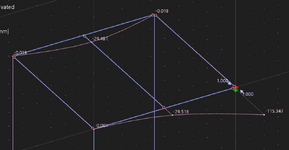

To first study how the frame provides torsional restraint to the column, I removed the column, and left only a rigid set of elements to represent the column section. I then applied a force couple to the flanges:

The mechanism by which the system resists torsion can be seen:

The beam connected to the column flange deflects about 115 mm. This shows that clearly this arrangement does not provide much rotational stiffness to the column.

To compare, I repeated the analysis with the column elements in place. Now the flange displaces about 9 mm. So clearly the stiffness comes only from the rotational stiffness of the column, and the beams don't provide any additional stiffness.

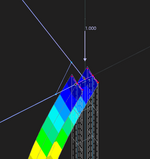

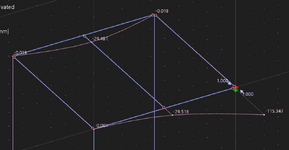

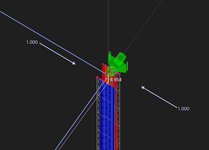

Turns out that the situation can be helped by stiffening the frame on plan. I added a small truss member between the beams:

Now the sideways displacement of the column flange is only about 0.3 mm, which is clearly stiffer than just the column.

So, the thing I'm thinking about: Is the torsional restraint to columns typically analyzed in some way? Or is just assumed that the stories are stiff enough in plan that columns are torsionally restrained? My local code (Eurocode) at least does not seem to provide any guidance on this, or how much stiffer the connection and framing should be in comparison to the column rotational stiffness to be able to consider the column torsionally restrained.

Often the effective length of a column in steel frames is taken as the story height. This applies not only for flexural buckling, but also for lateral-torsional and pure torsional buckling.

I'm currently reading the design guide "Worked examples for the design of steel structures" by Building Research Establishment, Steel Construction Institute and Ove Arup and partners. There is an example of how to calculate the lateral-torsional buckling resistance of a column in a steel frame. The illustration of one critical column in the frame is given as below:

Lateral-torsional buckling of the column is checked, because the eccentricity of the beam-column connection introduces bending moment in the column.

The authors continue to calculate the critical moment of the column assuming that the lateral-torsional buckling length of the column between levels is the story height (4 meters in this case). Per my understanding, buckling length for LTB is taken as the member length between torsionally braced points (sometimes called "fork" support). That is, the member should not be free to rotate between those points.

I'm curious, does this type of arrangement really provide full (or any) torsional restraint to the column at the story levels?

I wonder where the torsional support to the column comes from at all. The fin plate connection in the worked example surely does not provide a moment connection to the beam. I set out to do a small FEM calculation to study the rotational restraint provided by beams to the column in a similar situation.

The frame dimensions are 10m x 10m x 10m. All profiles are HEA200, with S355 steel having E = 210 GPa. Bracing of the frame is hidden for clarity.

The column studied is the rightmost one in the picture above. In detail, it looks as follows:

One beam is connected directly to the column web. The other is connected to the column flange. The section where the beams connect to the column is considered rigid. This section is supported in XY plane, without any Z-direction or rotational restraint. The beams are connected with pin conditions to the column around both X and Y axis.

To first study how the frame provides torsional restraint to the column, I removed the column, and left only a rigid set of elements to represent the column section. I then applied a force couple to the flanges:

The mechanism by which the system resists torsion can be seen:

The beam connected to the column flange deflects about 115 mm. This shows that clearly this arrangement does not provide much rotational stiffness to the column.

To compare, I repeated the analysis with the column elements in place. Now the flange displaces about 9 mm. So clearly the stiffness comes only from the rotational stiffness of the column, and the beams don't provide any additional stiffness.

Turns out that the situation can be helped by stiffening the frame on plan. I added a small truss member between the beams:

Now the sideways displacement of the column flange is only about 0.3 mm, which is clearly stiffer than just the column.

So, the thing I'm thinking about: Is the torsional restraint to columns typically analyzed in some way? Or is just assumed that the stories are stiff enough in plan that columns are torsionally restrained? My local code (Eurocode) at least does not seem to provide any guidance on this, or how much stiffer the connection and framing should be in comparison to the column rotational stiffness to be able to consider the column torsionally restrained.