I am somewhat new to using skin elements to account for moments at the junction between plates and solids, but I believe I'm doing it correctly. Yet the stress distributions I see have stark discontinuities and are nothing like what I would expect in the real world. My intuition is confirmed when re-modeling in 100% tet solids. Furthermore the max stress predicted by the hex/plate/skin combo is ~30% less than the tet model.

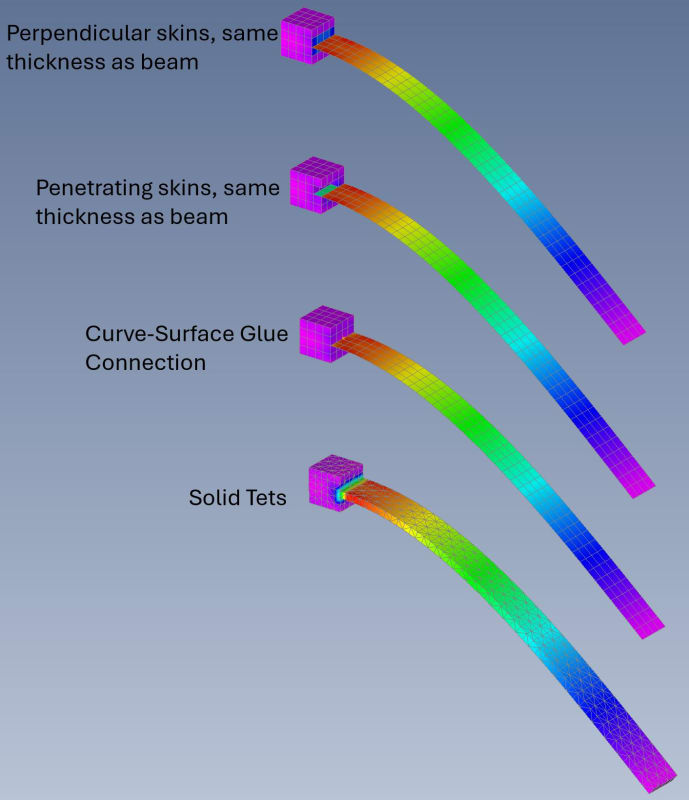

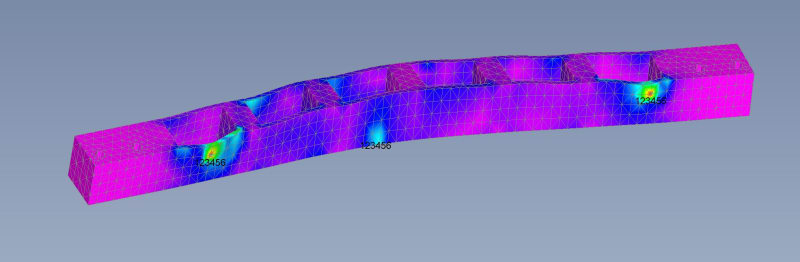

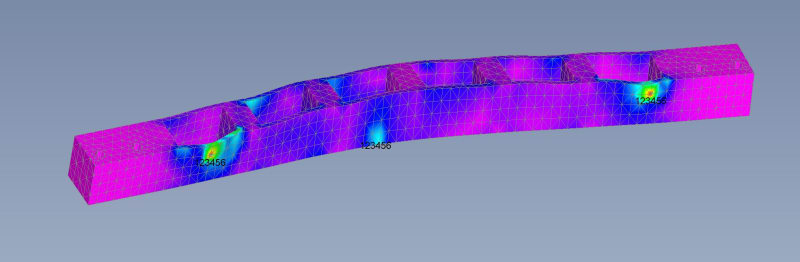

Stress results one would intuitively expect, modeled with all solid tets:

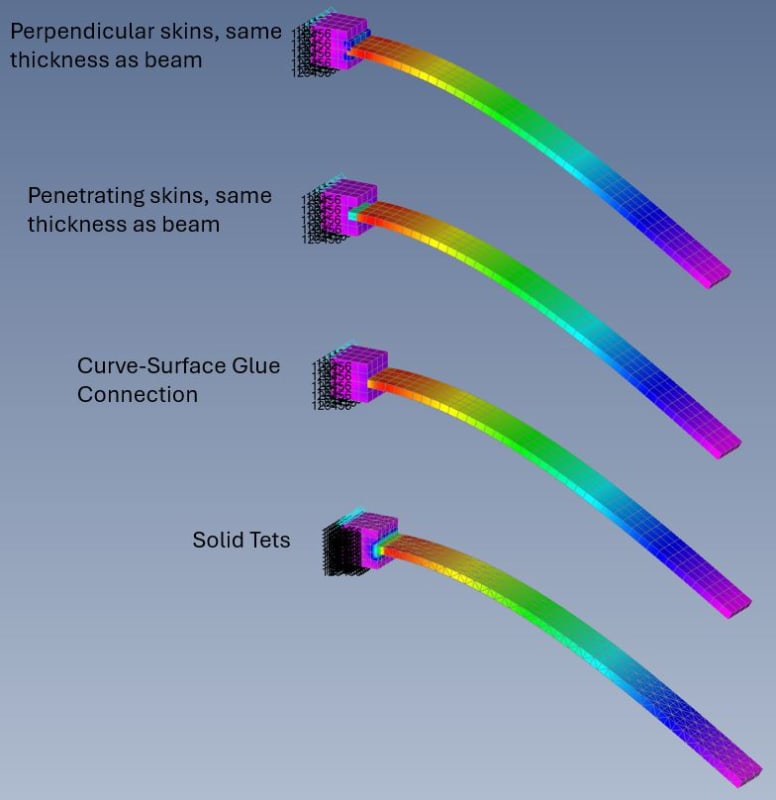

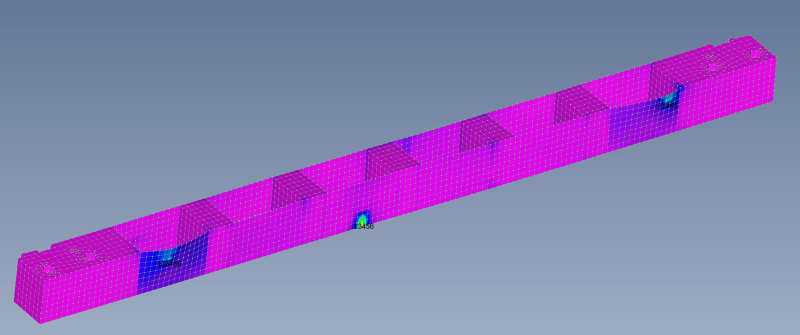

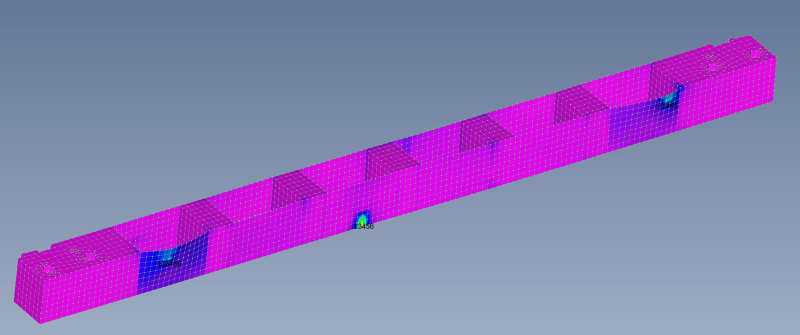

Stress results using plates and hex solids skinned with thin plates:

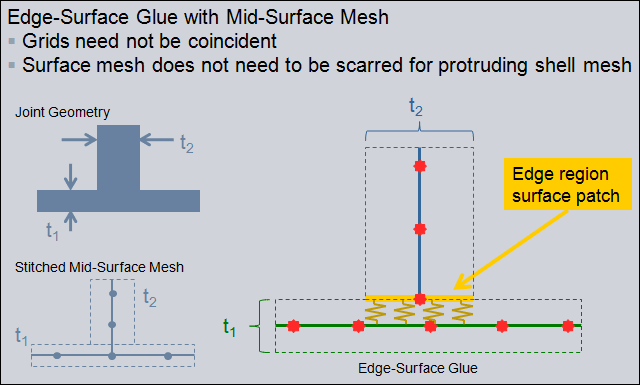

When I think about it, it makes sense that an extremely thin plate element would bend easily and you would see huge stress discontinuities, despite constraining the moments. But somehow I was under the impression that skin elements are a perfectly fine way to build efficient models that give mostly realistic stress distributions. Was I wrong to assume this? Am I somehow setting up the skin elements incorrectly?

Stress results one would intuitively expect, modeled with all solid tets:

Stress results using plates and hex solids skinned with thin plates:

When I think about it, it makes sense that an extremely thin plate element would bend easily and you would see huge stress discontinuities, despite constraining the moments. But somehow I was under the impression that skin elements are a perfectly fine way to build efficient models that give mostly realistic stress distributions. Was I wrong to assume this? Am I somehow setting up the skin elements incorrectly?