ChickenBake

Structural

- Jun 26, 2024

- 6

I have a couple of questions on one of the provisions that has been added in ACI 318-19. The clause on 17.1.6 states:

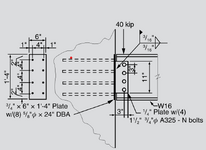

It is common in my world to specify embed plates with DBAs to facilitate connections between steel beams and the ends of walls or columns. The design philosophy is that the DBAs are extended a full development length into the wall and the connection is designed using the ACI Chapter 22 shear friction provisions for concrete against steel. Chapter 17 limit state checks are never done. If concrete breakout was checked, this would almost never pencil. See attached for an example detail.

Questions are as follows:

I am curious if other firms have encountered this issue yet. The internet appears to be mostly silent.

The commentary to the same section states:Reinforcement used as part of an embedment shall have development length established in accordance with other parts of this Code. If reinforcement is used as anchorage, concrete breakout failure shall be considered. Alternatively, anchor reinforcement in accordance with 17.5.2.1 shall be provided.

As an alternative to explicit determination of the concrete breakout strength of a group, anchor reinforcement provided in accordance with 17.5.2.1 may be used, or the reinforcement should be extended.

It is common in my world to specify embed plates with DBAs to facilitate connections between steel beams and the ends of walls or columns. The design philosophy is that the DBAs are extended a full development length into the wall and the connection is designed using the ACI Chapter 22 shear friction provisions for concrete against steel. Chapter 17 limit state checks are never done. If concrete breakout was checked, this would almost never pencil. See attached for an example detail.

Questions are as follows:

- What is the difference between reinforcement as "part of an embedment" and reinforcement "used as anchorage?" If they're the same, why does the clause use two different terms?

- If I am using the shear friction provisions, do I still need to check concrete breakout?

- Why does the code suggest extending the reinforcement as a solution instead of calculating the breakout capacity of the group? Extending the bars beyond development length would have no effect on the calculated Chapter 17 shear breakout capacity, and if you were talking tension, you wouldn't be able to determine what that extension should be without actually doing the calculation.

I am curious if other firms have encountered this issue yet. The internet appears to be mostly silent.