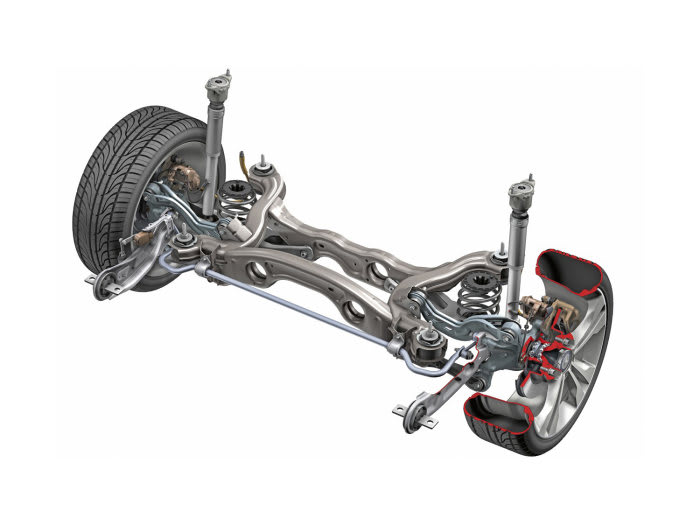

Lots of modern vehicles use something like this. Ford Focus "control blade" suspension was an early example, but VW Golf Mk5 and onward (those which use multilink IRS and not a twist-beam axle), 2016-on Honda Civic, are the ones that I have some familiarity with.

The trailing link locates the knuckle fore-aft (X) and in side-view (X-Z plane) rotation (think "trailing arm" but in side-view only - the trailing link is the one that absorbs braking torque). It does not locate the knuckle in toe or camber or laterally - that's the job of the lateral links. The trailing link is intentionally flexible in the directions that it does not serve a locating function (or taking up braking torque). Sometimes the trailing link is (almost) a flat piece of sheet metal to encourage flexing in the directions that it needs to flex. Sometimes it's attached to the knuckle with bushings that allow some "give". It is not over-constrained, because the trailing arm is designed to flex in the directions that it needs to.

The two lower links locate the knuckle in toe. The rear one is much longer than the front one, because remember, the knuckle is rotating in the X-Z plane, so with suspension up-down movement, the rear link travels much further up and down than the forward link does. Roughly speaking, in top view, the chassis-end pivots of the rear lateral link, the front lateral link, and the trailing link are in line. Usually the front lateral link will be a little shorter than this, in the interest of encouraging toe-in with both bump and rebound travel, which is the same as saying toe-in in roll. (Roll understeer)

The two lower links are pretty close to parallel in top view. This means the trailing link chassis-end bushing can be soft, because slight fore-aft movement of the knuckle (due to bushing deflection from bump impacts, or from braking) produce almost no toe change of the knuckle. This is better for separating the NVH forces from the handling forces. The lateral-link bushings can be stiff with little impact on NVH.

That the trailing link is very short, means there is a lot of anti-dive (in the rear, anti-lift) in braking. Because the forward drive torque reaction is not done in the knuckles (whether it's front-drive, or rear-drive with the diff bolted to the subframe), this doesn't lead to excessive anti-squat during acceleration.

The upper link just has to provide the desired camber in response to bump travel (or body roll).