I cannot provide a date when lamellar tearing became a less significant issue in our industry, but your general perception is correct. It is much less of an issue than it once was. I have worked in the steel industry for over twenty years, and I have never personally been involved with a project where lamellar tearing occurred. I have only heard of a couple potential instances of lamellar tearing over that time period.

The following statements in AISC documents support the idea that lamellar tearing is less of an issue today than it once was:

• Section 5.4 of AISC Design Guide 21 (a free download for members from

http://www.aisc.org/dg)

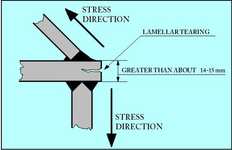

addresses lamellar tearing and states, “Current steel-making practices have helped to minimize lamellar tearing tendencies. With continuously cast steel, the degree of rolling after casting is diminished. The reduction in the amount of rolling has directly affected the degree to which these laminations are flattened, and has correspondingly reduced lamellar tearing tendencies… The incidence of lamellar tearing today is significantly reduced as compared to the past, due mostly to proper joint selection and better steel chemistry.”

• The Manual states, “Although lamellar tearing is less common today, the restraint against solidified weld deposit contraction inherent in some joint configurations can impose a tensile strain high enough to cause separation or tearing on planes parallel to the rolled surface of the element being joined… Dexter and Melendrez (2000) demonstrate that W-shapes are not susceptible to lamellar tearing or other through-thickness failures when welded tee joints are made to the flanges at locations away from member ends.”

Neither the 2016 Specification nor its Commentary mentions lamellar tearing. There is no requirement in the Specification to UT the base metal. There are requirements to UT CJP welds in Section N5.5. There are also toughness requirements in Sections A3.1c and 1d.

Section J6.2c of the Seismic Provisions includes requirements to UT base metal in some instances. There are no pre-fabrication UT requirements and the post-welding requirements apply only to specific conditions. It states, “After joint completion, base metal thicker than 1½ in. (38 mm) loaded in tension in the through-thickness direction in T-and corner-joints, where the connected material is greater than ¾ in. (19 mm) and contains CJP groove welds, shall be ultrasonically tested for discontinuities behind and adjacent to the fusion line of such welds. Any base metal discontinuities found within t/4 of the steel surface shall be accepted or rejected on the basis of criteria of AWS D1.1/D1.1M Table 6.2, where t is the thickness of the part subjected to the through-thickness strain.”

While the Specification for Safety-Related Steel Structures for Nuclear Facilities does not contain UT requirements for base metal, it does acknowledge that the engineer of record may wish to impose project-specific requirements. Section NA3.1d states, “The project specification covering material for structural components that, as a result of proposed welding procedures, design details, etc., are susceptible to lamellar tearing shall, as determined by the engineer of record, include the requirement that the material shall be either ultrasonically examined in accordance with ASTM A578/A578M, Level C, or tested in tension in the through-thickness direction (z-direction). The resulting percentage reduction in area in the z-direction shall not be less than 90% of that in the direction of material rolling.” A User Note states, “In determining the need for prefabrication inspection and the inspection acceptance level, the engineer should consider the geometry of the joint, the material type and grade, the anticipated quality of the material, and other experience factors. See Chapter NN. Lamellar tearing is generally caused by the contraction of large metal deposits with high joint restraint; lamellar tears seldom result when weld sizes are less than ¾ in.”

I also recently worked with a colleague and an individual working at a U.S. mill to write the following for an article that may be published in the near future:

“Lamellar tearing is one consideration related to this anisotropy. Several factors play a part in lamellar tearing, including joint configuration and steel chemistry. The manufacturing process itself also plays a role. The current steel making practice of continuous casting places demands on the producer that have the benefit of controlling the shape of inclusions and improving through-thickness strength. Therefore current continuous cast products have less likelihood of lamellar tearing than older ingot cast product did. Engineers can reduce the likelihood of lamellar tearing through good design practice, as described in Design Guide 21. Material specifications define some aspects of chemical composition, such as limits on sulfur, which can be objectively evaluated assuming the proper expertise, but the details of the manufacturing process may be more difficult to know and to evaluate.”