greznik91

Structural

- Feb 14, 2017

- 186

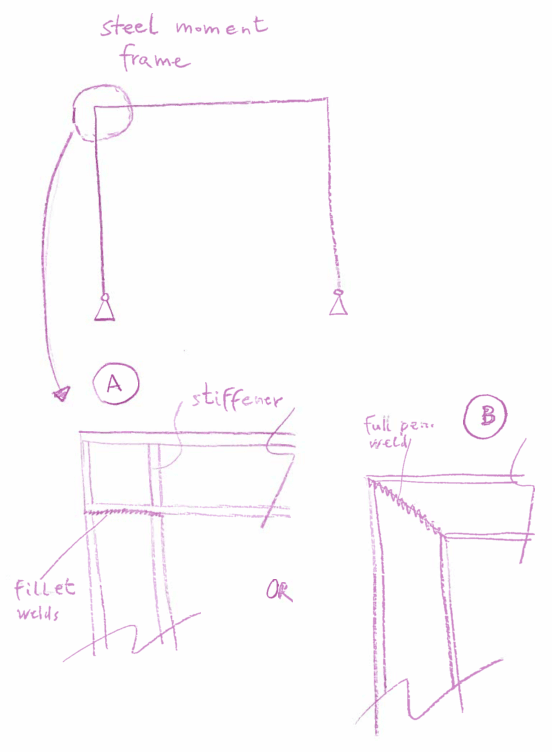

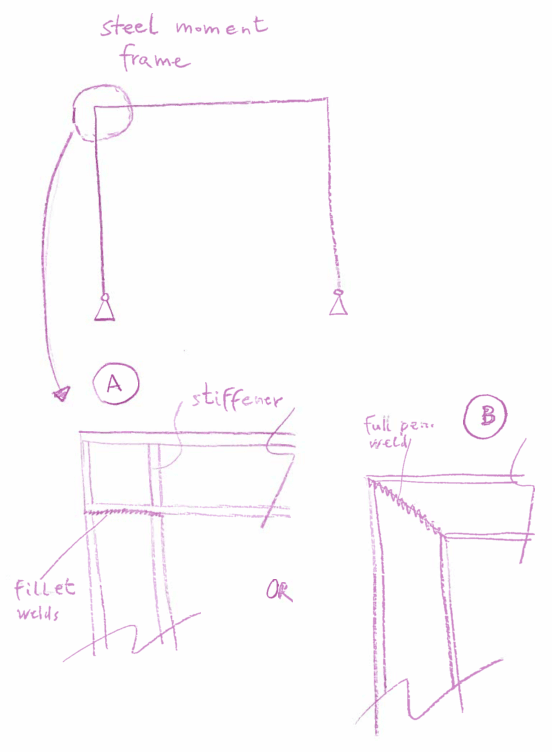

How stiff is a moment steel frame with full penetration weld between column - beam (sketch B) compared to a connection shown in case A where beam is welded to a column with stiffeners. When to use connection B over A? I am not a fan of connection B - I think Id use it only for frames that are not that loaded?