1) Not that you asked but this is the paper that introduced me to tension chord bracing:

Link.

OP said:

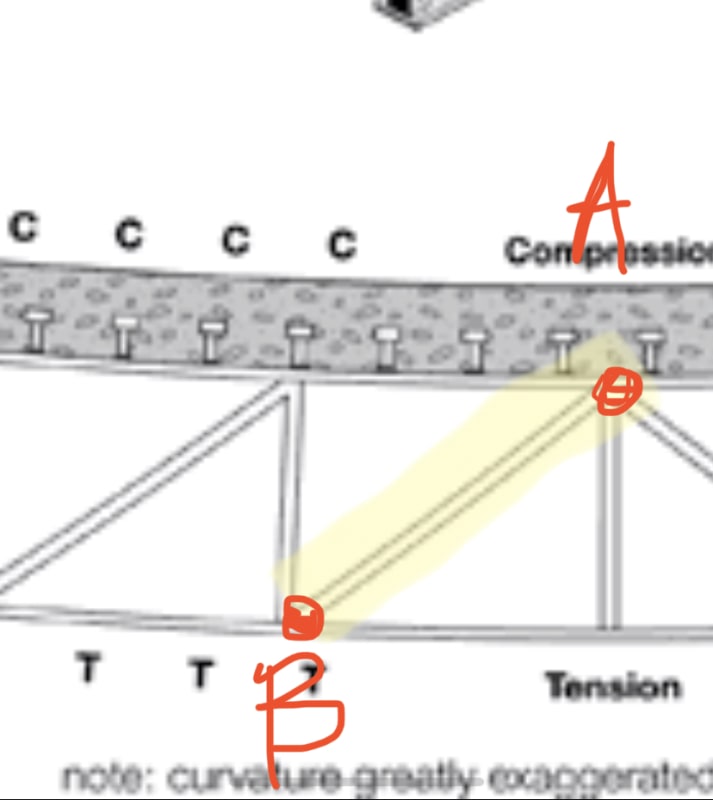

2) For very light, top chord supported truss of the sort that would normally be called

open webbed steel joists in north america, I do feel that the bridging is important for this reason, among others. And the

Steel Joist Institute prescriptive provisions on bridging seem to be mostly in line with my expectations in this regard. I like to see, at a minimum, two lines of bracing near the ends of these kinds of trusses, sometimes more for longer spans.

3) Curiously, I've seen numerous examples in the wild of short floor joists trusses with only a single line of bracing at mid span. This flies a bit counter to the voice of my intuition which tells me that you'd at least want two lateral bracing points on the bottom chord so that that bottom chord can brace the compression webs in a spanning, girt-ish fashion like the bottom flange of a steel beam. With just one brace point at mid-span, it feels like the bottom chord would just want to spin around that. As I'll get into below, there are mechanisms of tension flange buckling resistance other than the girt-ish one and I recognize that they increase capacity and would sometimes be helped by a single line of bracing. Still, I like the girt-ish mechanism for ease of evaluation if nothing else.

4) There are some trusses that simply need to not have their tension chord braced for architectural reasons. Exposed steel trusses over conference centers, sexy heavy timber trusses... stuff like that. They're out there and seem to work. In studying these situations myself, I've come to the conclusion that the self weight of the bottom chord itself is often adequate to brace the tension flanges of heavy trusses. Additionally, where a concrete slab is in play and/or the top chord is an HSS etc, torsional stiffness can help out a fair bit with the bracing function.

5) I've come to view the question of truss tension chord buckling as quite analogous to wide flange beam lateral torsional buckling. Rather than ask "why does a tension chord buckle?", I ponder "why

doesn't a tension flange buckle?". The answer is, of course, that wide flange beams generally have a much more favorable combination of torsional stiffness and code mandated rotational support at the ends. It's an interesting parallel regardless however. I've also considered this explicitly for beams used as

josit substitutes where you basically top flange hang your beam to match the depth of your joists seats and, thus, rob it it of much of it's normal end rotational restraint (snipped below).

OP said:

And I doubt very much that the bottom chord can withstand any lateral kick.

Technically, the bottom chord doesn't

need to withstand a lateral kick from a stability perspective. Rather, it only need to return to it's original position when you're done kicking it.