canwesteng

Structural

- May 12, 2014

- 1,693

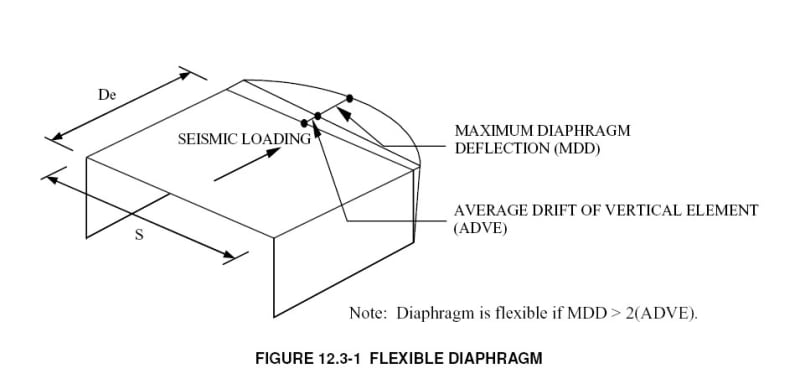

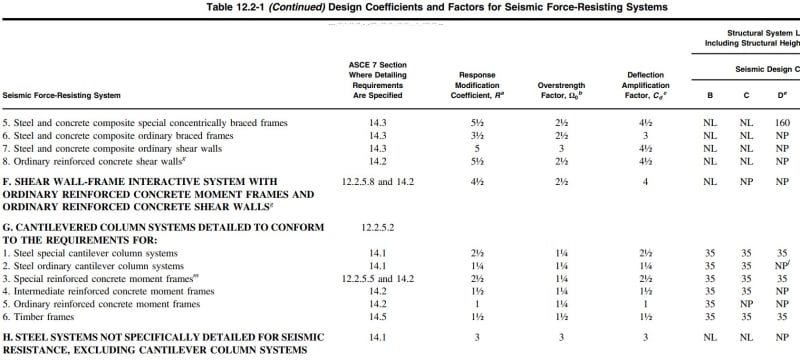

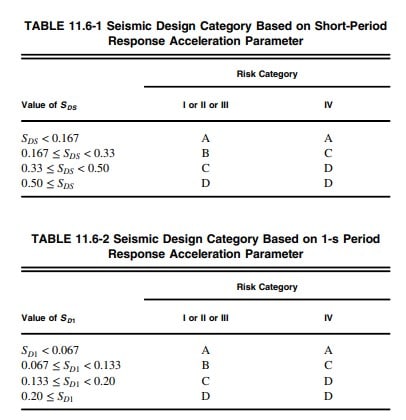

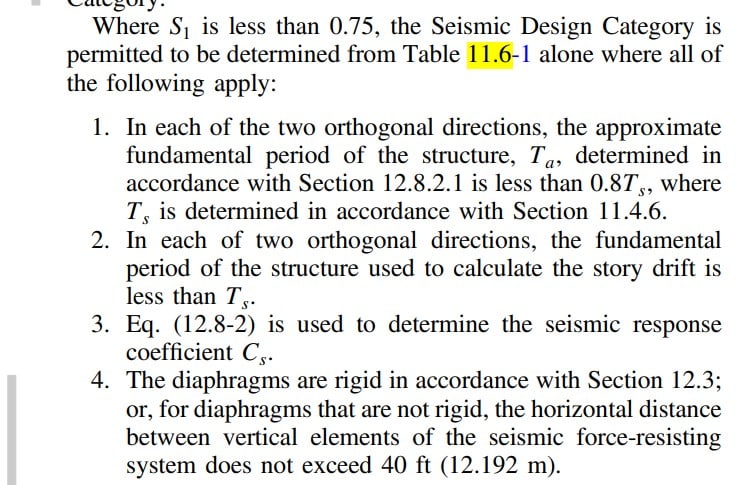

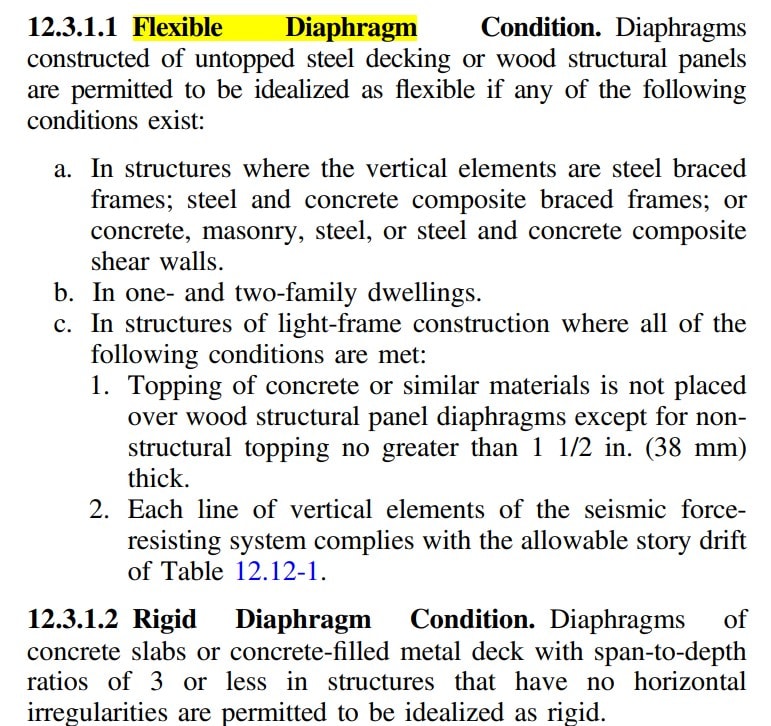

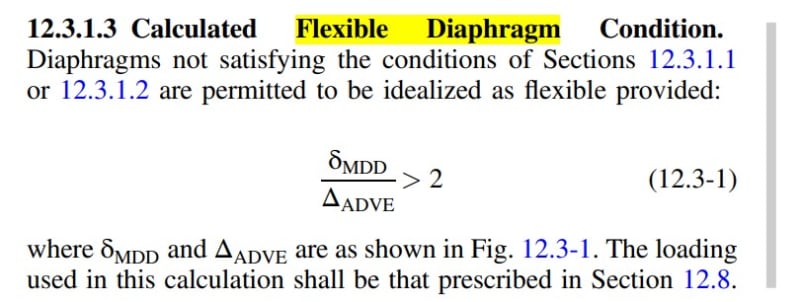

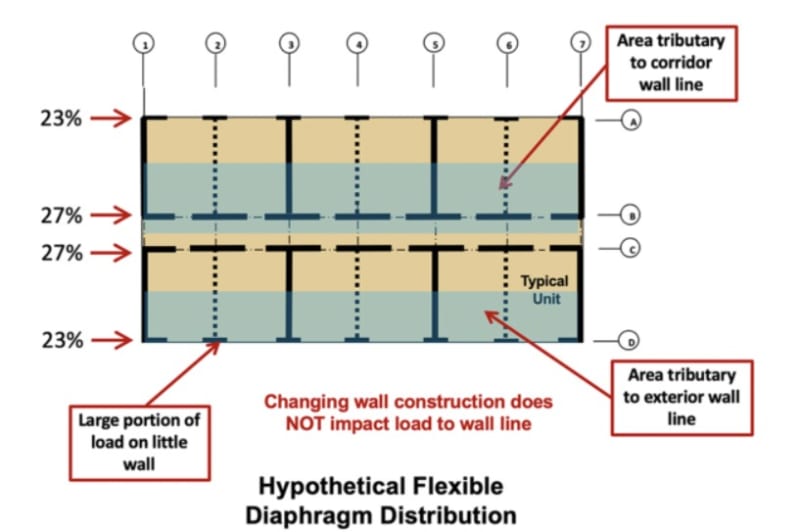

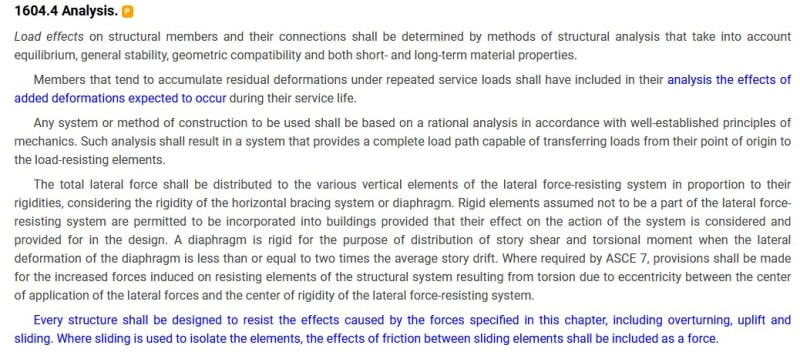

Section 11.6 allows us to use only table 11.6-1 to determine the SDC, which in my case lets me go to SDC C from D, which is pretty desirable. It points to 12.3 for the rigid diaphragm conditions, which seems to be only allow concrete deck to be called rigid. I'm wondering if there is any way justify calculating the actual stiffness of my diaphragm in order to call it rigid - I've come up empty handed so far.