Forgot2Yield

Industrial

- Feb 10, 2022

- 68

I constantly here non-engineers complaining about how everything structural engineers design is so unnecessary and overkill. It is hard to explain to someone unfamiliar with design codes and engineering theory why certain members need to be sized the way they are sized even if using a smaller member (or no member at all) would not cause the structure to fall down.

I am wondering if anyone has had any discussions with members of the non-engineering community around this topic, and how you explained to them that the seemingly unnecessary sizes of the components are indeed necessary.

My personal explanation includes three main reasons. Please add to this if you have more.

1) Proof

any design that you come up with, you have to be able to show or prove what the forces in the members will be. and If you don't have all the information to start out with (ex. proper loads) then you have to make educated approximations of this missing information that will almost always be conservative. People always say, "it's not going to fall down, it's common sense, just look at it, others were built just like it and they are still standing". But if you can't prove it through applied scientific principles or scientific models, you can't just say its fine no matter how overkill it looks.

2) Time

For most of the designs that I work on, there are very short timelines for projects. These short timelines mean that there is not enough time to do proper analysis on the entire structure so some vary broad assumptions get made. And the broader the assumption, the more conservative it has to be. The less time that is available to analyze, the more excessive the design becomes

3) Code

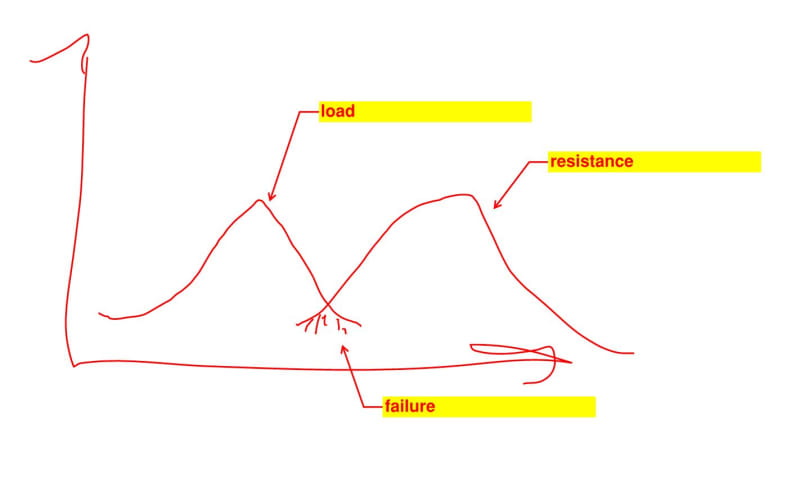

Specifications like the ANSI/AISC 360, CSA S16, ACI 318, CSA A23 which get incorporated into building codes specify exactly what strengths you are allowed to assign to members. Given that inelastic and plastic analysis is allowed to be used, time often only permits the use of linear elastic analysis in my case. This is one item that always gets brought up. In a linear elastic analysis the member fails, but in reality the forces will be redistributed throughout the structure to different members. If you don't have the time, tools, or expertise to do more complex analysis, and you are stuck with first order linear elastic, you can't rely on the force being redistributed, because you can't show it.

I am wondering if anyone has had any discussions with members of the non-engineering community around this topic, and how you explained to them that the seemingly unnecessary sizes of the components are indeed necessary.

My personal explanation includes three main reasons. Please add to this if you have more.

1) Proof

any design that you come up with, you have to be able to show or prove what the forces in the members will be. and If you don't have all the information to start out with (ex. proper loads) then you have to make educated approximations of this missing information that will almost always be conservative. People always say, "it's not going to fall down, it's common sense, just look at it, others were built just like it and they are still standing". But if you can't prove it through applied scientific principles or scientific models, you can't just say its fine no matter how overkill it looks.

2) Time

For most of the designs that I work on, there are very short timelines for projects. These short timelines mean that there is not enough time to do proper analysis on the entire structure so some vary broad assumptions get made. And the broader the assumption, the more conservative it has to be. The less time that is available to analyze, the more excessive the design becomes

3) Code

Specifications like the ANSI/AISC 360, CSA S16, ACI 318, CSA A23 which get incorporated into building codes specify exactly what strengths you are allowed to assign to members. Given that inelastic and plastic analysis is allowed to be used, time often only permits the use of linear elastic analysis in my case. This is one item that always gets brought up. In a linear elastic analysis the member fails, but in reality the forces will be redistributed throughout the structure to different members. If you don't have the time, tools, or expertise to do more complex analysis, and you are stuck with first order linear elastic, you can't rely on the force being redistributed, because you can't show it.