The section basically says

1 - 11.2.1(a) (i) and (ii) if the wall is fully in compression design it as a wall or as a column depending on simplified method versus rigorous.

2 - 11.2.1(b) (i) if the wall goes into tension on one face and is acting as a flexural member, design is as a column in combined axial force and moment

3 - 11.2.1(b) (ii) if the wall goes into tension on one face and it is non-flexural, design it as a deep beam i.e. strut tie.

The old code said the same things, but was more convoluted and harder to understand, eg it suggested for 2 above designing as a beam in accordance with section 8, which does not account for axial compression, so how could you do it, other than to then go to section 10 that accounted for combined axial and compression. The old rule did not make sense. The new one says to go to section 10.

And for 2 and 3 above which was a combined sentence in the old code, it left it to the designer to decide between the 2 options "as appropriate". Maybe people who now do not understand the new code did not understand what was appropriate in the old code and always designed them as columns, incorrectly.

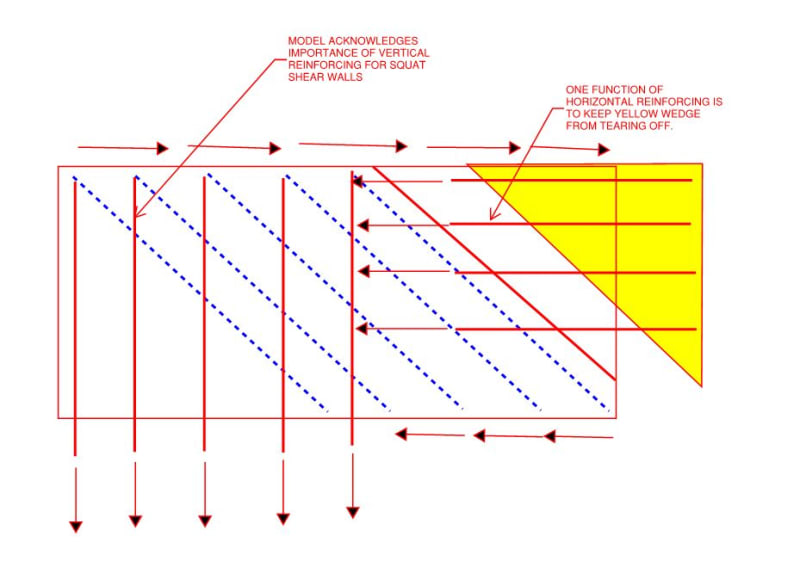

If a wall is 3m tall and 3m long, you cannot design it as a column. It is a deep beam. It has to be designed in accordance with section 12.

That is what "as appropriate" was telling you to do previously, design it in accordance with section 12 in AS3600-2009 clause 11.2.1(b) last sentence!

Nothing has changed in this except the code now defines when section 12 should be used instead of allowing the designer to decide "as appropriate" when they did not understand what was appropriate!