There is no reason (yet) to believe the crew turned the STAB TRIM back on.

I have been seeing some misinterpretations and misunderstandings. I don't want the speculation and assumptions to get out of control. Without saying I'm the best person to explain this, I think I'm in a good position to discuss some of the details about the control system. I hope to forestall any jumping to conclusions about what the crew may or may not have done. While I acknowledge that my own understanding of the 737 is limited, I have been taking the time to read carefully the most authoritative sources of information, so that I may understand it better.

Assumptions that "electric trim" implies MCAS is turned on are incorrect.

Assumptions that "manual" control of a device implies no electric operation are also incorrect.

Even though the 737 is a fairly old aircraft type, it's not only controlled by rods and strings.

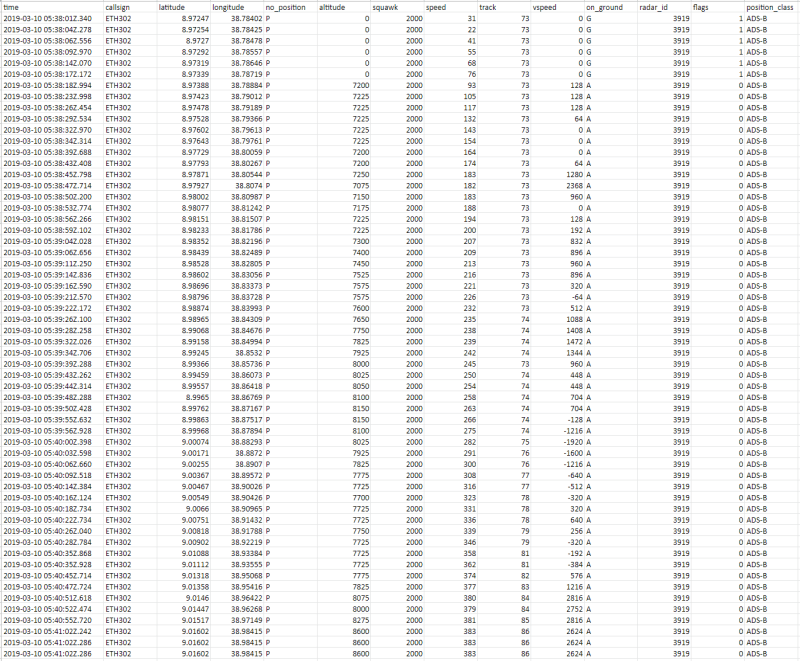

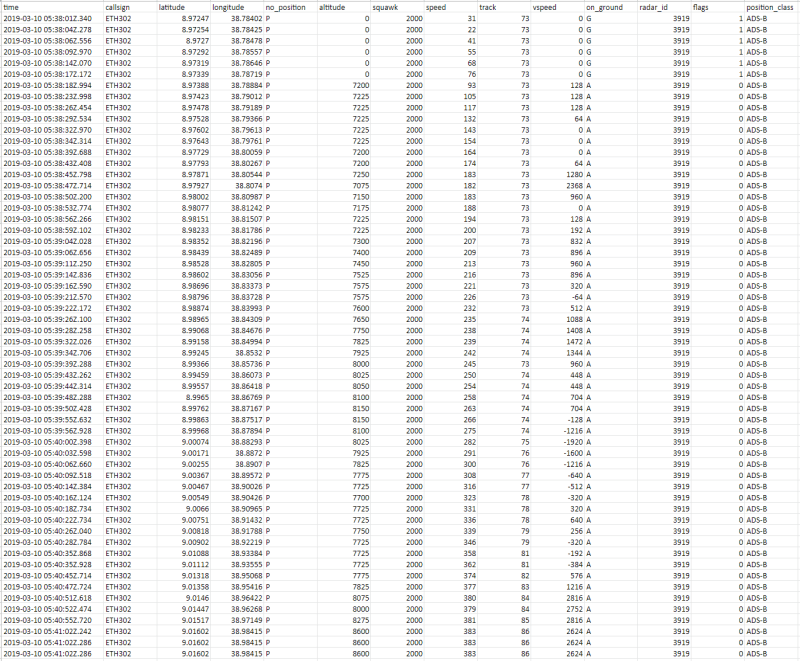

The sequence of events told in the preliminary report indicates that the "manual (electric) trim" was used at

The "old" 737's were equipped with autopilot, yaw dampers, mach trim, and approach coupling as standard equipment. These automatic systems are similar to the systems used today, and driven by semiconductor logic that a modern engineer can read and follow. They've probably evolved over the decades, but I don't think they've been replaced outright.

When operated in manual mode, the automatic systems are overridden, as you would expect, but manual doesn't mean "mechanical".

Here's a photo of the relevant controls:

This picture was taken just a few years ago from a 737-400. As you can see from all the glass, it's had an avionics upgrade, but the basic flight controls remain the same.

The 737's all have stabilizer trim wheels on either side of the center console to allow the flight crew to make manual adjustments to the stabilizer. These adjustments are unnecessary when the autopilot is on, and moving the wheels can actually disable the AP if it is.

In the lower center of the photo, you can see the pair of STAB TRIM switches. If they are set to CUTOUT then the autopilot and hence approach coupling cannot engage. Also disconnected by STAB TRIM CUTOUT is the MCAS. What remains available, however, are the manual trim, MACH trim and the Yaw dampers.

Mach trim does what you might assume it does: adjusts the trim slightly for the effects of high speed (the 737's fly up to Mach 0.85 or so). The Yaw dampers compensate for oscillations in the aircraft's lateral direction which happen when slight adjustments are made to its direction. There is no need to override these if the stabilizer trim has trouble (and reasons why you don't want to either).

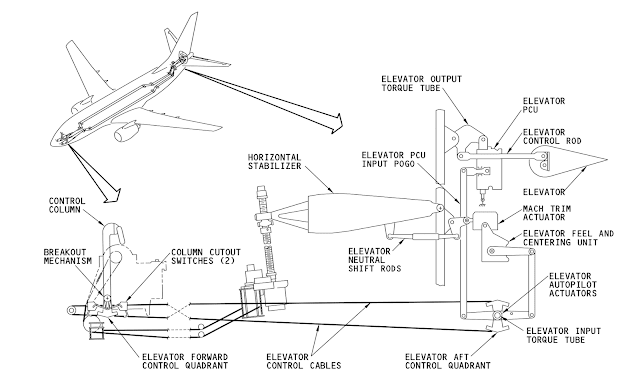

The aircraft stabilizer and elevator work in a dependent-independent relationship. The stabilizer is the "entire" horizontal tail, which can pitch up or down several degrees. You can see the marks on the fuselage this travel leaves on every 737. When the stabilizer moves, the elevators moves, too. Their relative movements are complex:

(The above photo is from a 737-200. Sorry I have no 737 Max schematics. It is my belief that much of this system is similar on later aircraft, including the Max, but I admit it's an assumption on my part.)

The main driver of the horizontal stabilizer is the trim actuator, which is a screw-jack. It receives commands from trim adjustment wheels on the center console. My understanding is that on the Max, an additional input to this actuator is sent from the MCAS system. When active, the MCAS will move the actuator, adjusting the stabilizer pitch up (which pitches the nose down) and the crew should expect to see the stabilizer wheels spin at the same time.

The elevator is the movable trailing edge of the stabilizer. The main control Yoke operates the elevator, and it is quite true that this is done by steel cables. So when the flight crew "pulls back on the stick" they are indeed pulling on cables and directly moving the elevator. You can also see from the schematic above, there are other systems acting on it, including the mach trim and the autopilot actuators. These make adjustments relative to the position of the cables from the yoke, and the elevator can move under autopilot control without the yoke showing any corresponding movement.

So going back to what happens when the STAB TRIM is set to CUTOUT, the autopilot actuators on the elevator stop working, and so should the MCAS control over the stabilizer trim. But all the other controls do still function.

I believe the ET-AVJ crew had properly set these switches to CUTOUT, and never moved them back. They then wrestled the yoke bring the nose back up, but it took all their personal strength to do so. When one or the other tried a couple of times to reach for the trim wheel on the console, he could only manage a small amount of turn before he had to put his hands back on the yoke to maintain the nose attitude. This was tried twice but the effect was too small. They would have had to accomplish many turns of those wheels to return the stabilizer to a neutral position.

No one believes the theory except the one who developed it. Everyone believes the experiment except the one who ran it.

STF