Alistair_Heaton

Mechanical

- Nov 4, 2018

- 9,781

This thread is a continuation of:

thread815-445840

****************************

Another 737 max has crashed during departure in Ethiopia.

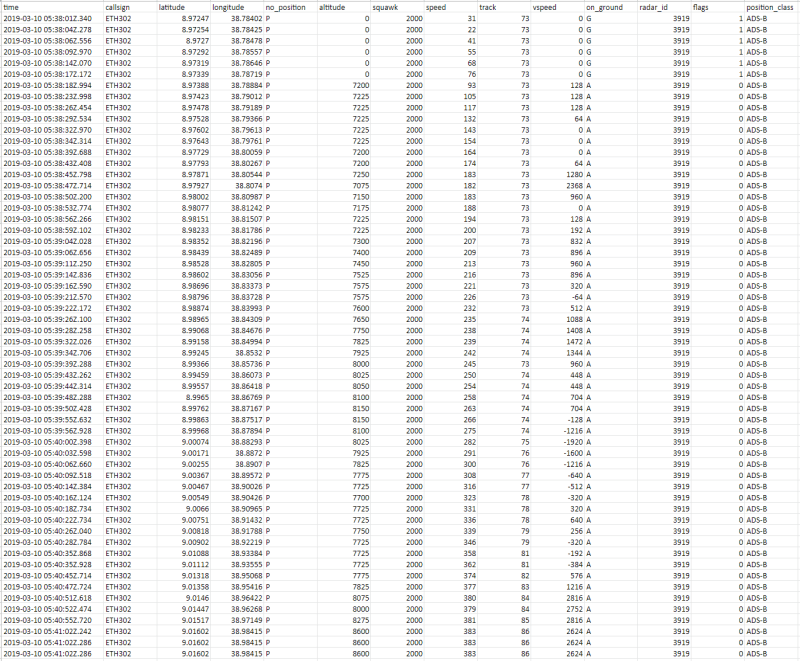

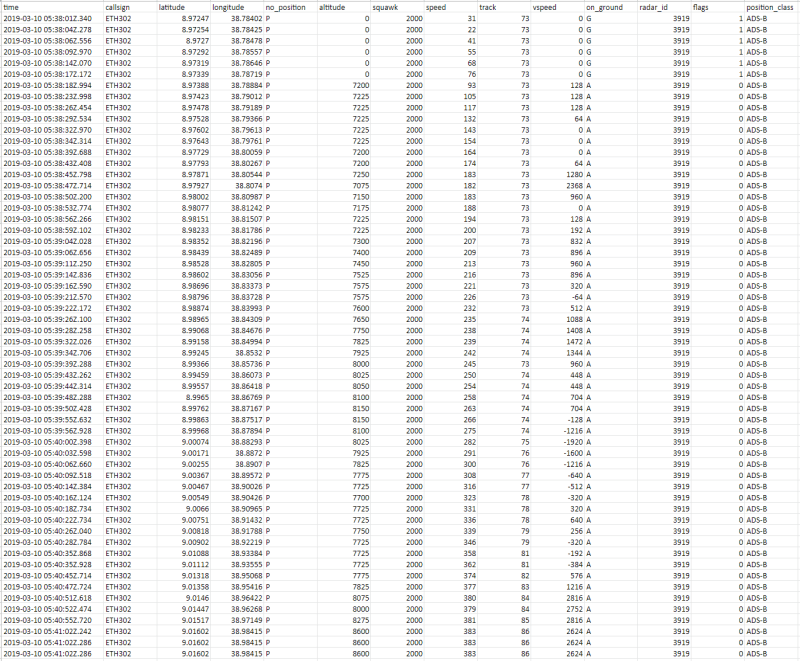

To note the data in the picture is intally ground 0 then when airborne is GPS altitude above MSL. The airport is extremely high.

The debris is extremely compact and the fuel burned, they reckon it was 400knts plus when it hit the ground.

Here is the radar24 data pulled from there local site.

It's already being discussed if was another AoA issue with the MCAS system for stall protection.

I will let you make your own conclusions.

thread815-445840

****************************

Another 737 max has crashed during departure in Ethiopia.

To note the data in the picture is intally ground 0 then when airborne is GPS altitude above MSL. The airport is extremely high.

The debris is extremely compact and the fuel burned, they reckon it was 400knts plus when it hit the ground.

Here is the radar24 data pulled from there local site.

It's already being discussed if was another AoA issue with the MCAS system for stall protection.

I will let you make your own conclusions.